If there was one capitalist in Chicago who wasn’t about to be told what to do by the “Knights of Labor” or by the Bricklayers’ union it was George M. Pullman. Pullman was granted a building permit to construct a nine-story building on April 17, 1883, only seventeen days into the bricklayers’ strike, meaning that Beman had been working on the building for quite some time before the strike began. A strike was not going to stop Pullman and two weeks later, in the midst of the work stoppage, Pullman decided to break ground for what was touted as Chicago’s most expensive private office building.

Beman had reached the ripe old age of thirty when Pullman had asked him in early 1883 to design his first office building in Chicago’s business district. This was no small task, for it was to be Chicago’s largest private office building. Characteristically, Pullman bucked the trend to move into the Board of Trade area, for Pullman had no love for Vanderbilt or his companies after the Commodore had gained total control of the Michigan Central in 1875 and proceeded to cancel the line’s contract with Pullman in order to replace the Pullman cars with those of his major competitor, Webster Wagner, so it would have been logical for Pullman to want to be as far away as possible from the La Salle Street station.

Although Pullman’s site (170′ x 127′) was slightly smaller than the Burlington’s, characteristically, Pullman wanted to add three floors of apartments (Pullman lived in his mansion at 1729 S. Prairie Avenue, the NW corner of Prairie and 18th, diagonally across from where the Glessners will build their home in 1885) and private dining spaces to the Burlington’s six floors of office space, resulting in another of Chicago’s early mixed-use projects (including the Central Music Hall). In essence, his building was conceived as a stationary, but much larger Pullman Palace Car, once again following the “Pullman system.” To top off this challenge for Beman, Pullman’s ego also demanded that his building be the tallest privately-owned building in the city, something that Beman was already used to with the Pullman water tower. Faced with the design of such a new building type for the first time, Beman evidently studied the work of the firms most experienced in such projects, George Post and Burnham & Root. His design of the Pullman Building can be understood as taking the organization and massing of Post’s Mills Building, wrapping it with the single window, monochromatic brick and terra-cotta language of the only completed ten-story office building in Chicago at the time, Burnham & Root’s Montauk Block, and then turning the all-important corner of Michigan and Adams with the corner Post had designed for his earlier Post Building.

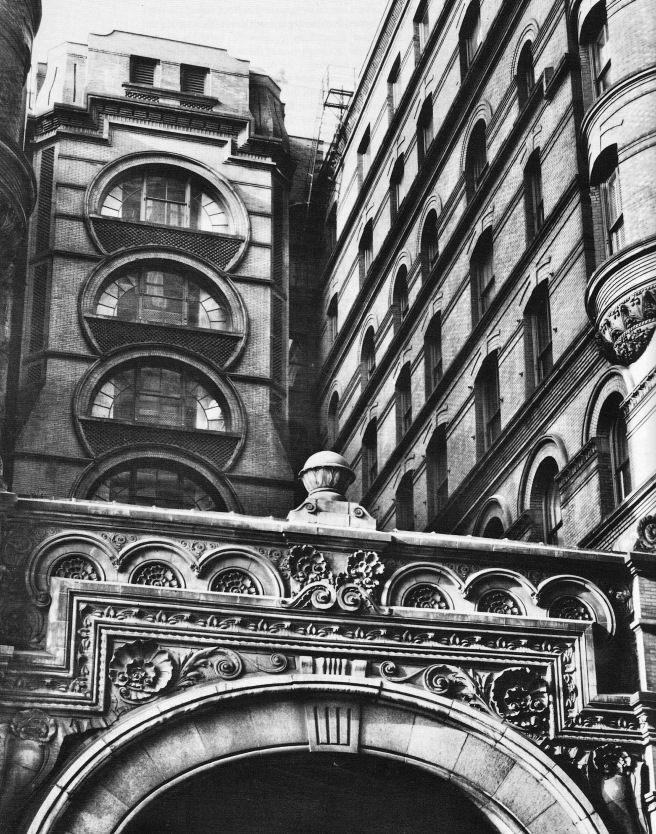

At the same time, however, he rejected the radical palazzo or box-like forms of the Mills and Burlington Buildings in favor of a more traditional picturesque roof profile. Undoubtedly, Pullman wanted a more unique image for his corporate headquarters than what he thought a speculative office building looked like (ignoring the fact that the Burlington Building was just the opposite). Also echoing both of Post’s buildings, Beman positioned the external light-court over the building’s elliptical-arched entry portal on Adams Street that broke this elevation into two awkwardly unequal masses, similar to the Post Building.

Beman’s inexperience with such a large building, however, had placed the lightcourt on the wrong side of the building. Instead of placing it ideally on the south side in order to minimize the loss of light from projected shadows, he had located it as a formal device on the entrance or north side, which meant that during the winter most of the windows lining the court would have been in perpetual shadow of the low sun. Again, similar to Post’s Mills Building, an exterior entry court that was covered with a skylight led from the arched portal to the building’s entrance staircase.

These were flanked by a double stairway that, along with its railing, was detailed in an ahistoric-styled, double-curved manner that appeared to foreshadow the upcoming Art Nouveau period (as did the column capitals at the entrance). Another unique feature in Beman’s design was his use of the 3/4 circle in the stacked windows that marked the building’s circulation spine.

The lower six floors were organized as following: First-the company’s purchasing agent and rentable shops along the Adams Street front;

Second-the offices for the company’s primary officers with Pullman having, of course, the corner window overlooking the Exposition Center (the entry courtyard and the grand stairway, therefore, provided the primary entry to this piano nobile-like organization);

Third-the offices for the company’s second-tier officers; Fourth-the offices for Gen. Philip Sheridan, who had been named on Nov. 1, 1883, as the Commanding General, U.S. Army, as well as the offices for the Headquarters for the Army’s Division of the Missouri. His office was the corner office, only two floors above that of Pullman’s, providing a formidable watchtower, indeed! This location for Sheridan, directly across the street from the Exposition Building, and within the confines of the Pullman Company, was meant by Pullman, I believe, to send a simple but direct message to Chicago’s nascent “Communards.” The Fifth Floor was occupied by the offices of both the Chicago and the Central Union Telephone Companies, while the Sixth was dedicated to private rental offices for professionals. Two elevators off the Adams Street lobby serviced these six floors.

The top three floors contained over 75 well-appointed apartments, varying in size from 10 rooms for families to two rooms for bachelors. While primarily intended for employees, any available apartment could be rented by those not affiliated with the company. The residential floors were accessed through a separate lobby off Michigan Avenue that also provided the use of two elevators. The ninth floor also contained the equivalent of a Pullman Dining Car: the Albion, a first-class restaurant located in the rear of the building that included private dining rooms, a parlor, and a reading room. (These floor plans are posted on the Pullman Museum site and are thought to have come from an 1884 sales brochure printed by Turner and Bond, the agents assigned to rent the building.)

The kitchen for the restaurant was located in a partial tenth floor, that also contained housing for the servants, at the rear of the building. All of these floors were serviced with steam heat, provided by equipment that was located in the building’s basement, with the exception of the boilers, that were moved to a separate out-building in order to minimize any damage caused by an explosion. Most of the apartments were also provided with a fireplace, that was evident in the tall chimneys that lined the cornice of the building.

The building’s structure was “boxed,” that is a brick box, with windows cut into the walls that completely enclose the iron-framed (fireproofed by the Pioneer Company) interior. Beman’s use of single windows and red terra-cotta sillcourses at each floor to articulate the St. Louis red pressed brick elevations as a series of one-story, horizontal layers, tends to point to his study of the Montauk Block as his point of departure. Fortunately, Pullman was willing to spend more money than was Peter Brooks, that allowed Beman to transcend the Montauk’s pedestrian language with a freer use of a variety of window heads.

In fact, in the eight floors above the base, he employed four different window heads: Fl. 2-segmental arch recessed within a rectangular frame; Fls. 3,7,8-segmental arch with one of my favorite details, a projected keystone that sprouted an arched rib; Fls 4,7-semicircular arch; and Fl. 9-flat-headed. There was no functional relation between the type of window head and the floor it occurred on (i.e., to differentiate between the corporate offices, the speculative offices, and the residential floors). In the Montauk Block, Root at least had a formal idea that gave the elevations a perceptible order, Beman’s elevations were random. While the shear quantity of different details spoke to Pullman’s Victorian “picturesque” aesthetic of “the more, the better” (for more evidence of this, look up the interiors of his mansion), one gains a better appreciate for Owen Jones’ call for repose in a building’s design when studying Post’s elevations for the Produce Exchange or Root’s elevations of the Burlington Building.

Beman also employed the Montauk’s battered stone base in red granite along Michigan Avenue, but once it turned the corner onto Adams Street, he opened it up into a arcaded loggia that, unfortunately, did not connect to the main entrance court. Beman made turning the corner a wonderful architectonic event not only by placing a 45′ high turret (inspired by Hunt’s Vanderbilt house and Root’s recently-completed Calumet Club) at the corner that completed the building’s record 165′ height, but also by recessing the walls on either side of the corner in a manner that vertically continued the curve of the turret all the way to the building’s stone base. The only exception was the eighth floor that was allowed to wrap around the corner of the building as a continuous surface, that made it appear to be a bracket that held in place the turret and its curved corner bay.

FURTHER READING:

Leyendecker, Liston Edgington. Palace Car Prince: A Biography of George Mortimer Pullman. Niwot, CO: University of Colorado Press, 1992.

Schlereth, Thomas J., “Solon Spenser Beman,” Zukowsky, John (ed.), Chicago Architecture: 1872-1922, Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1987, p. 173-187.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)

Another good source for information regarding the Pullman Building is Irving K. Pond’s autobiography. Pond defines the role that he and John Edelman had in some of the building’s decorative features. He also discusses how it was was George Pullman who suggested to S. S. Beman Post’s Mills Building as a model — Pullman’s New York office was in the Mills Building. Apparently, Beman wanted to place the court on interior (facing south) and it was Pullman that suggested having the court face north, looking out onto Adams street and offered the Mills Building as a model.

LikeLike