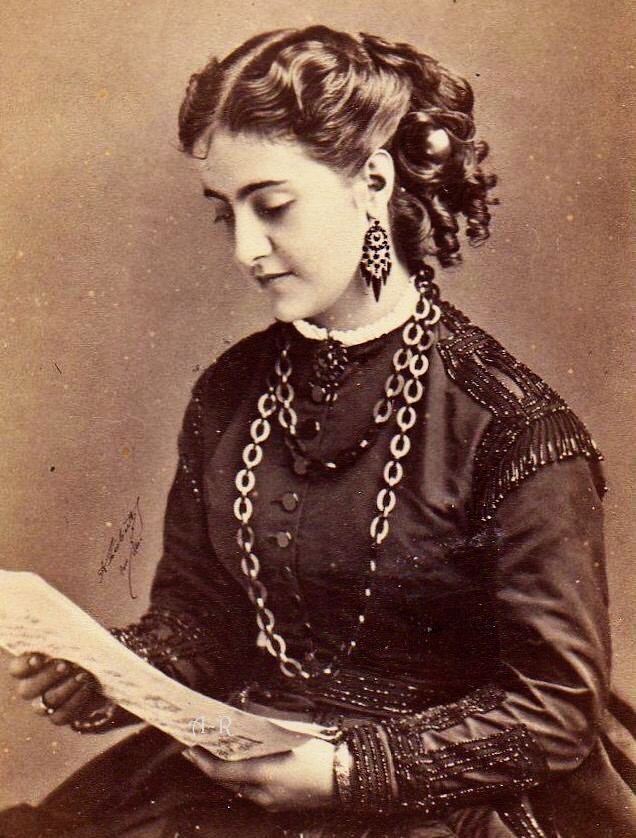

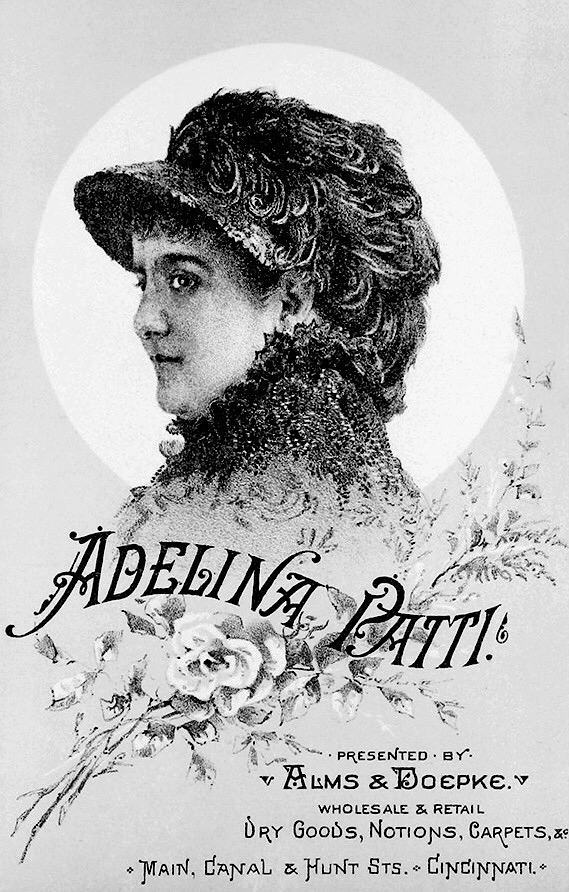

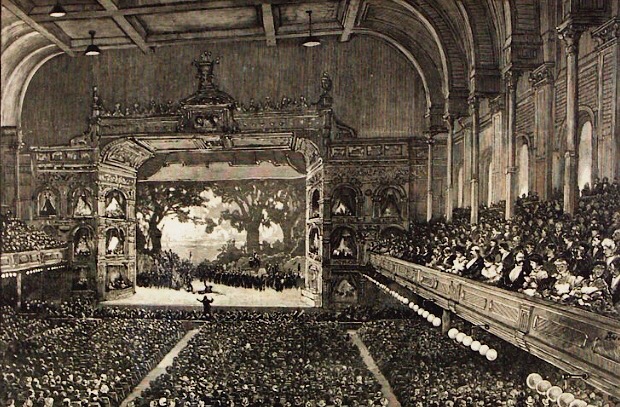

While Theodore Thomas had resigned from Cincinnati’s College of Music, he remained committed to the Cincinnati May Festivals throughout his life. The overwhelming success of this biennial event had led Cincinnati’s cultural elite to expand into Grand Opera, seemingly in response to New York’s inception of the Metropolitan Opera. Cincinnati had a head start in this competition, however, for while New York still had to construct a major music hall for Grand Opera, Cincinnati already had its majestic Music Hall. Mapleson was named the impresario of the Cincinnati Grand Opera Festival and convinced to bring his star, world-famous soprano Adelina Patti, along with his Covent Garden troupe in February 1881 to Music Hall. Although born to Italian parents who at the time lived in Spain, the family had moved to New York where she learned to sing, making her operatic debut at the Academy of Music in 1859. At the age of 16 she had been brought to London by Mapleson to make her European debut, where she remained for the next twenty years. Finally, in February 1881 Mapleson brought her back to the U.S. for a homecoming tour. I cannot ascertain whether she played first in New York, which is what I expected happened, or she debuted in Cincinnati. Either way, her appearance assured Cincinnati’s huge auditorium would be packed to the rafters, shaming Chicago’s music community to react as best it could. (It was reported that some Chicago opera buffs had taken the train to Cincinnati to hear the diva.)

Meanwhile, Mapleson would continue to bring his Covent Garden troupe, sans Patti, each January to Chicago to play in Haverly’s Theater (note that the new Central Music Hall was not used by Mapleson) to smaller and smaller crowds each year. N. K. Fairbank once again reacted to the events in Cincinnati by organizing the Chicago May Festival Association that same February of 1881, while Cincinnati’s first Grand Opera Festival was in full force, to plan a music festival for the following year similar to Cincinnati’s eight-year-old May Festival, including inviting its disillusioned director Theodore Thomas to lead it. As local choral groups rehearsed, the Tribune mused “whether Chicago in the future will have a chorus distinctively its own, and as intimately identified with the city as the Cincinnati chorus is with that city.” Mapleson returned to Cincinnati with Patti in February 1882 for the second Cincinnati Grand Opera Festival, where she once again enchanted all who heard her sing the role of Aida on Valentine’s Day and closed the Festival on Saturday, Feb. 18, in the role of Leonora in Verdi’s Il Trovatore. So Patti had played Cincinnati twice before Chicago could stage its first May Festival.

10.7. THE CHICAGO 1882 MAY FESTIVAL

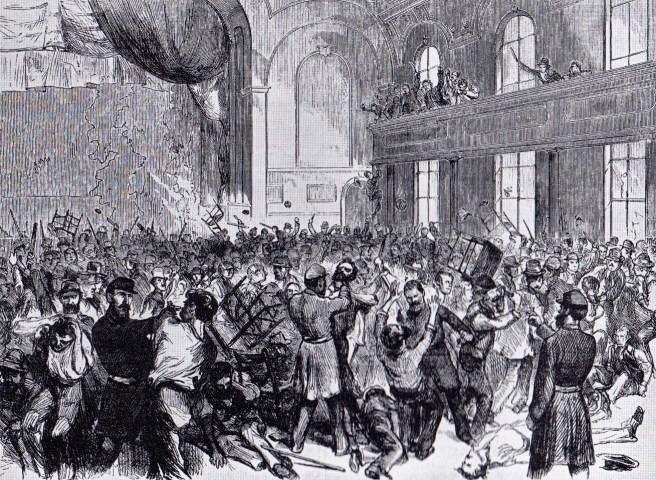

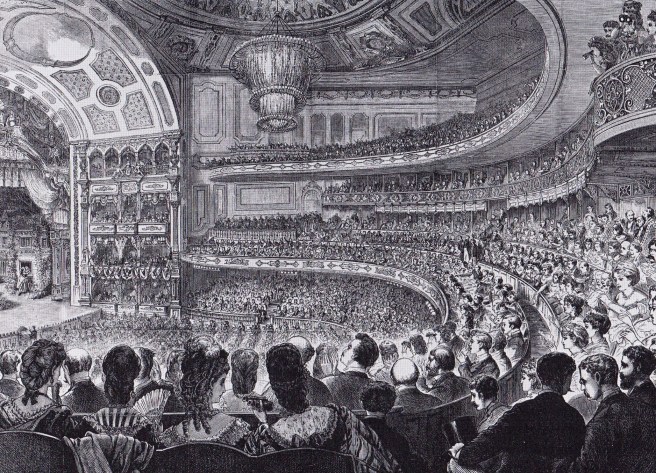

The following month, meanwhile, saw Chicago’s Socialists commemorate the eleventh anniversary of the Paris Commune with another “monster rally” in the Interstate Industrial Exposition Building in March 1882, only two months before Fairbank’s May Festival Organization was scheduled to use the same building to house the first Chicago May Music Festival during May 23-6, 1882. In essence, the struggle over the Expo Building in 1882 summarized the battle being waged in Chicago between its business elites and the city’s growing Socialist movement. Fairbank once again turned to his trusted friend, Dankmar Adler to design a temporary hall in the antiquated Expo Building for the 1882 May Festival. Adler was given the south end of the building for his installation that comprised of a sounding board similar in design to the one Thomas had designed back in 1877, and seating for 6500 built in sections on raised platforms. Access tunnels to the seats were painted in a variety of colors that matched the tickets so that the audience could easily locate their seats. Adler’s valiant attempt notwithstanding, however, the vast Expo Building had not been designed for musical performance and the music simply disappeared into the air:

“The people were there; but did not hear the music… It may be reasonably doubted that more than ten percent of those who were present heard any soloist as they should all have been heard, or felt the chorus and orchestra [carry] to their ears the complement of harmony necessary for genuine pleasure… The readiness with which business men advanced the cost of the festival, and the actual popularity of the concerts, even in severe weather, indicated that Chicago people are eager to enjoy music of the highest character. They have not yet had an opportunity to do so… The opportunity cannot arrive until a suitable structure, like that of which Cincinnati justly boasts, shall be erected.”

The final kiss of death for the concerts that May was provided by the Illinois Central locomotives as they whistled and chugged by during the performances less than 100’ to the east of the glass-enclosed structure…

10.8. FAIRBANK FAILS ONCE MORE TO GARNER PRIVATE MONEY TO BUILD A MUSIC HALL IN CHICAGO

Nonetheless, encouraged by the over the 45,000 who had attended the festival during the four days in May, Mapleson finally brought Patti to Chicago for her debut the following January 1883. The successive reduction in ticket sales that he had been forced to swallow over the past two of his annual Chicago appearances in Haverly’s Theater, however, led him to lease the smaller McVicker’s Theater (1800 seats vs. 2500 seats) to insure a sold house at the higher price that a Patti performance would command. The $20 price for all six nights, in which Patti made but only one appearance, precluded all but the very rich from attending what many had thought should have been uplifting entertainment for those in the middle and lower classes, some of which had attended the preceding May Festival. If these people were ever to enjoy such entertainment, Chicago would eventually have to erect a structure similar in size and acoustic quality to that of Cincinnati’s Music Hall:

“The Academy of Music needed [in Chicago] must be erected by public spirit alone [as was Cincinnati’s], for no one pretends to think or say that it will be a good financial investment. It must be large, with excellent acoustics, central in location, with exits on three sides possible – nothing else can give satisfaction or benefit the community. Such a building devoted to art and music would make it possible for the middle class to hear opera and not become paupers.”

Indeed, N.K. Fairbank as early as 1880 had pledged to give $100,000 towards a permanent music hall if nine other similarly-minded businessmen would each match his pledge. None had come forward. (Remember that five years earlier Cincinnatian Reuben Springer had personally donated over $250,000 toward the cost of the Music Hall in 1877 during the lowpoint of the Depression.) Following Patti’s Chicago debut, Fairbank, with the support of one or two other like-minded individuals, had again made this offer, but again Chicago’s leading businessmen were still simply too tightfisted to give this kind of money for a civic institution.

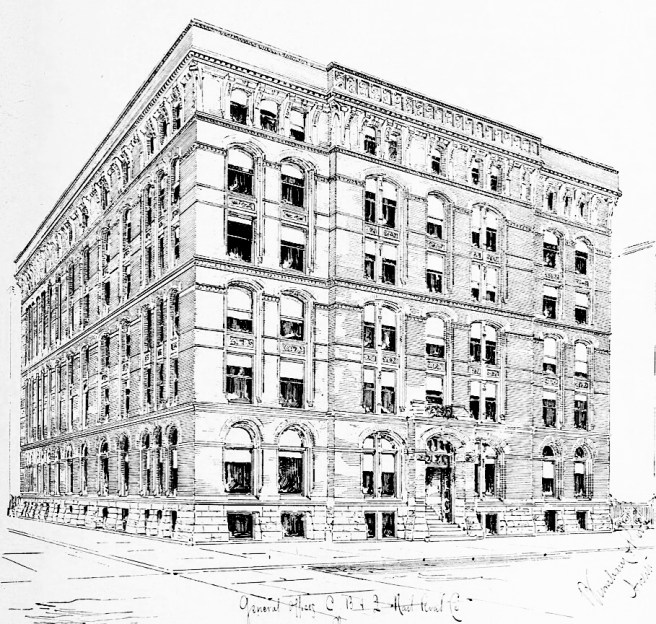

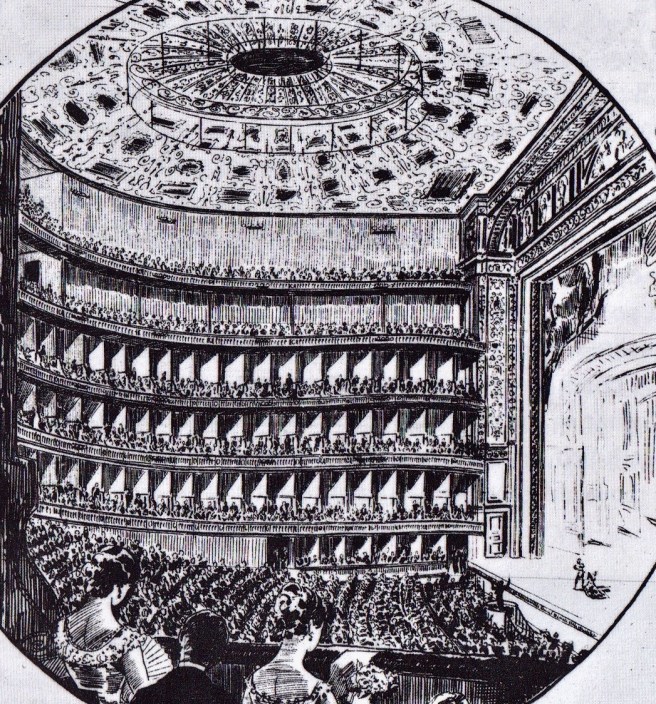

10.9. THE FOUNDING OF THE METROPOLITAN OPERA

The contrast with New York at precisely this moment couldn’t have been starker. While Chicago’s business leaders would not entertain Fairbank’s proposal, this was precisely what New York’s elites were doing in order to erect a new building for the new Metropolitan Opera. Following the incorporation of the Met’s stock company in April 1880, seventy families had donated $17,500 each through the purchase of shares in the company to raise $1.2 million. A loan of $600,000 completed the amount needed to construct the design of architect J. Cleveland Cady on the west side of Broadway, between 39th and 40th. It was completed in October 1883 with a capacity of 3,045 seats, many of which were located in private boxes that lined the first three galleries. As opposed to Cincinnati’s Music Hall that was designed on the exterior to look like a music auditorium in its park-like setting, however, Cady had to design the Met’s exterior as a downtown business building, similar to Adler’s exterior of the Central Music Hall. Its four-story central entry was flanked by seven-story pavilions on each corner whose upper five floors contained bachelors apartments, an inclusion to generate income towards the building upkeep.

As the Metropolitan Opera was established to be a rival for New York’s Academy of Music, where Mapleson’s Covent Garden troupe performed each November, an entire new opera company had to be formed in time for the opening of the new Metropolitan Opera building in October 1883. This responsibility was given to Henry Abbey, the former manager of Edwin Booth’s theater, who arranged to have the premiere of the new troupe on October 22 with Gounod’s Faust, starring Patti’s rival, the Swedish soprano Christina Nilsson.

FURTHER READING:

Siry, Joseph M. The Chicago Auditorium Building. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)