In v.3, sec.6.5, I discussed how the decision of the Santa Fe Railroad to extend its tracks to Chicago had finally reignited speculative construction in the business district after the two-plus year hiatus caused by the Haymarket Affair (while some historians credit the expectation that Chicago would be named the city for the 1892 World’s Fair, this decision was made more than a year after the announcement of the Santa Fe, and had only “poured gas on the fire” already set). The railroad owners had chosen to align its tracks with Dearborn Street, undoubtedly in conjunction with the long-term investment plans of the Brooks brothers, who already owned the Portland Block at the southeast corner of Dearborn and Washington. The original plan was to erect the Chicago & Western Indiana Station (the umbrella company formed to build the station for the numerous companies planning to use it) at the foot of Dearborn, on the south side of Harrison. Before these plans were announced, the Brookses had purchased a number of lots along Dearborn for future buildings. In addition to the lot for the Monadnock, they also secretly purchased the northwest corner of Dearborn and Harrison, immediately across the street from where these insiders were planning the erect the new station. Unfortunately for their bottomline, investors in La Salle Street properties had not only used their clout with City Council members to force the station to eventually be erected two blocks farther south at Polk Street, but also to stop the southward extension of Dearborn for over two years that, for all practical purposes, had prevented any construction along this southern stretch of “Dearborn.”

During the great construction boom of 1884-5, the Brookses’ agent, Owen Aldis, who was working with Burnham & Root in the early design of the Monadnock, was also working with Holabird & Roche to design a six-story building for the Brookses for the corner of Dearborn and Harrison. In Chapter Three, I had summarized how the young firm of Holabird & Roche came to be commissioned by Wirt Walker to design the Tacoma Building. Center to the early success of the firm was a personal connection with Byran Lathrop, Thomas Byran’s nephew and successor as the President of Graceland Cemetery, as well of many Byran’s other investments. Lathrop was the older brother-in-law of Owen Aldis, who at the time of Holabird and Roche forming their firm, had recently become the real estate agent for the Brooks, being responsible for commissioning Burnham & Root to design the Montauk Block. Lathrop, who maintained his Chicago office in the Montauk, had just arranged with his brother-in-law to offer Holabird & Roche the lease of the office across the hall from his, hence, the two aspiring architects had made the acquaintance of one of Chicago’s leading real estate agents. Aldis had given them a “test” commission of a small addition in 1884 before he then recommended them to the Brookses to design a six-story building for this corner of Dearborn and Harrison. Aldis had already contracted George Fuller to be the contractor, which is how the two firms met, prior to being commissioned by Wirt Walker to design and build the Tacoma Building. Anyway, their first Brookses’ project was a victim of the Haymarket slowdown of 1886-8, not be resurrected until 1889.

The facts reveal that Lathrop, Aldis’ brother-in-law was, more than likely, apprised by Aldis of the potential bonanza available in undeveloped Dearborn real estate and “jumped on the bandwagon” by buying an 80’ interior lot on the west side of Dearborn, at 508 S. Dearborn, only a few lots north of the planned location for the Brookses’ building. Lathrop logically commissioned Holabird & Roche to design the building. This occurred after construction had reached the halfway point on the Tacoma and followed the publication of the first renderings of Root’s final design of the Monadnock, so one can understand the design of the Caxton Building as the next iteration of the use of the combined iron frame with lateral walls/masonry curtain wall/bay window construction following the Tacoma Building and the Monadnock Block.

The lot was located in what was becoming Chicago’s relocated “Printing House Row,” so not needing any “design incentives” to entice renters, Lathrop settled for a “bare bones” design. As was the case with the two precedents, the narrow site once again cried out for bay windows to increase the rental floor area. With masonry party walls required on both interior edges of the lot, Holabird & Roche simply placed a 12-story steel frame with five bays/four lines of columns within the two party walls. The exterior “curtain wall” was as “plain” was the Monadnock’s; gone were the repetitive horizontal sillcourses of the Tacoma,

The only difference being the Caxton’s cornice was more traditional than Root’s radical coved profile. Holabird & Roche even reiterated Root’s design of the bay windows: these started at the third floor (whereas those in the Tacoma began at the second) and were stopped one floor lower that the top floor (again, as Root had done versus how they had allowed the Tacoma’s bays to extend into and disrupt the cornice). As what one may credit as having been a response to the negative comments about the Tacoma’s overabundance of glass, Holabird & Roche reduced the size of the windows in the two end bays, even though they, too, were skeleton-framed, thereby again echoing Root’s design. In fact, if one didn’t look at the first two floors, you were looking at a good copy of the Monadnock’s upper floors.

It was in the two lowest floors that a difference from the Monadnock was plainly evident. As they had done in the Tacoma Building, Holabird & Roche let the “thinness” of the steel frame open up these two floors: apparently it was not a “sin” to have too much glass along the siewalk in a building. As was the case in with the Tacoma Building, the building would have offered a completely different effect during the evenings and the long winter months of early darkness: the upper floors of the building would have appeared to be floating above the building’s luminous base. Le Corbusier and his “pilotis” of the 1920s had nothing on the early skyscrapers of Holabird & Roche.

Meanwhile, a few months later Shepherd Brooks decided to begin construction on the fourteen-story Pontiac Building only four lots south of the Caxton’s construction site, and three blocks south of where the Monadnock Block was under construction. Coming so close on the heels of the start of the Monadnock, and having the same owner, real estate agent, and contractor, one could view it as it as the half-sister of the Monadnock: half-sister because it was designed by a different architect, Holabird & Roche. Nonetheless, the Pontiac had many similarities with the Monadnock. In fact, one could speculate on how much of Burnham & Root’s iron-framed version of the Monadnock was incorporated in the design of the Pontiac (after all, both Aldis and Fuller would have had a set of drawings for this design…).

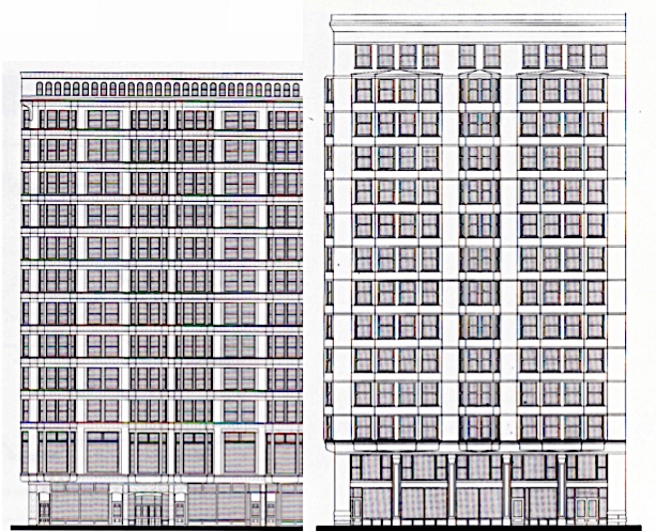

One immediate difference between the Monadnock and the Pontiac is the different exterior profiles. Even though both sites had the same 66’ width, while Burnham & Root had reduced the width of the upper floors by 30” which Root celebrated with the gentle curve in the elevation within the second story, Holabird & Roche simply extruded the entire width of the lot for the building’s height, as they had done with the Caxton Building.

Had Aldis finally understood, or at least suspected that the extra cost of all those curved bricks was not offset by the reduction in amount of floor area and wall surface in the final design of the Monadnock? Therefore, in massing, the Pontiac was just the elongation by two floors of the Caxton. (Even the start and stopping of the bay windows echoed the Caxton, that was a copy of Root’s in the Monadnock.)

In construction, Shepherd Brooks still clung to his aversion to all steel-framed exteriors but appears to have compromised somewhat. While the exterior steel framing of the Caxton was used in each of the three streetfronts, the building’s two corners on Harrison were solid load-bearing masonry piers. Although the building had a party wall on the north end, Holabird & Roche decided to place a lateral wall in the second interior columnline, as they had done in the Tacoma Building (and Burnham & Root had done in the Monadnock).

The apparent aversion to the ‘spindliness” of the wide-open elevations of the Tacoma (or had it been a reaction to the cold frost that had formed on the glass during the below zero Chicago winters?) had, as was done with the elevations of the Caxton, forced Holabird & Roche to reduce the amount of glass in the elevations of the Pontiac, giving it the more “solid” look of the Monadnock, even though these elevations were steel-framed. This was accomplished by making the bay windows smaller than the structural bay, filling in the space between the columns and the bay with a masonry partition (see plan).

As the elevations above show, Holabird & Roche once again decided to “open up” the elevations of the two stories closest to the sidewalk, revealing the steel frame supporting the floors above.Therefore, in all three buildings, Tacoma, Caxton, and Pontiac, the lower two floors would glow during the evenings and the dark, winter afternoons.

One detail that they brought over from the Tacoma was its horizontal accentuation of each floor. This was accomplished not with a projecting sillcourse, but with a course of larger terra cotta blocks set flush with the wall that connected the heads of the windows in each story.

One innovation they incorporated was the two structural bay-bay window. That is, rather than putting a bay window over only one bay, they stretched these bay windows over two structural bays, giving it a more fluid form than the one-bay windows also used on the exterior. The building code had specified only that bay windows could project no more than 36″ over the sidewalk; it never defined how “large” a bay window could be. Some historians say that this was to create more floor space, but the two-bay windows did not project as far out as the one-bay windows, so I don’t think this was the reason for this detail. Looking at the plan, they detailed a partition “panel” between the bay windows central mullion and the column. My guess is that, because of this “right-angle,” the two-bay window allowed better furniture placement than did the angular one-bay window. No matter, on the exterior the two-bay windows imparted a fluidity that recalled the surface undulations of the Monadnock.

To look into the future: Were Burnham & Root just too busy to take on another Brooks’ building (yes, in 1889 they were) or/and was Aldis giving Holabird & Roche the opportunity to show that they were capable of designing a successful large office building, in order to increase his covey of reliable architects. I read the events that came after to confirm both speculations. The facts are that following Root’s death, Aldis never commissioned D.H. Burnham & Co. to design another building for the Brookses. Hoffman stated that Aldis had complained, after Root had died, that the Monadnock came in way over budget as his reason for switching architects. With the Pontiac Aldis had the ability to compare similar buildings from a cost perspective erected by the same contractor, Fuller. However, as I will discuss in detail in Vol. Seven devoted to the 1893 Fair, I think the real issue was that Aldis truly enjoyed the opportunity to work with Root. He did not have the same enthusiasm for working with Burnham alone, following Root’s death.

FURTHER READING:

Bruegmann, Robert. The Architects and the City: Holabird and Roche of Chicago, 1880-1918. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Leslie, Thomas. Chicago Skyscrapers: 1871-1934. Urbana: University of Illinois, 2012.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)