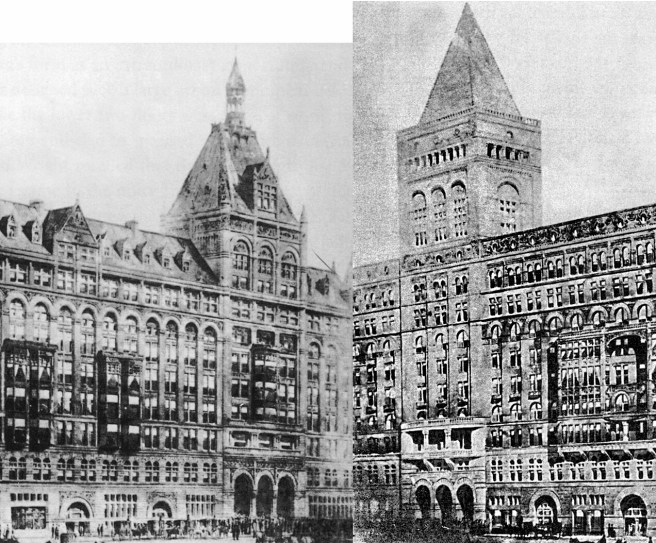

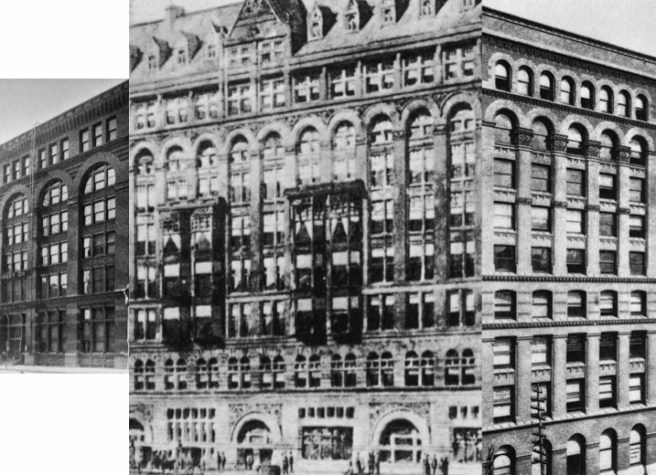

While Peck had succeeded in getting the President to come to Chicago for the Cornerstone parade, the 1888 conventions were another matter. True, Chicago had pulled off a minor miracle by hosting both conventions in 1884, but their return in 1888 was, by no means a foregone conclusion. Chicago’s monopoly in 1884 had only ignited the ambitions of its rival cities. St. Louis, that had lost its title of the “largest city in the West,” that it had wrestled from Cincinnati during the Civil War, to Chicago only after the 1871 fire, was finally beginning to appreciate the value/worth of “culture.” In 1883, more than likely after Chicago had bagged both conventions, the city began construction of a facility to challenge Cincinnati’s Music Hall, the St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall. Designed with a seating capacity of 3500 (vs. Cincinnati’s 3627), the entire facility covered over six acres and boasted an early installation of electric lights.

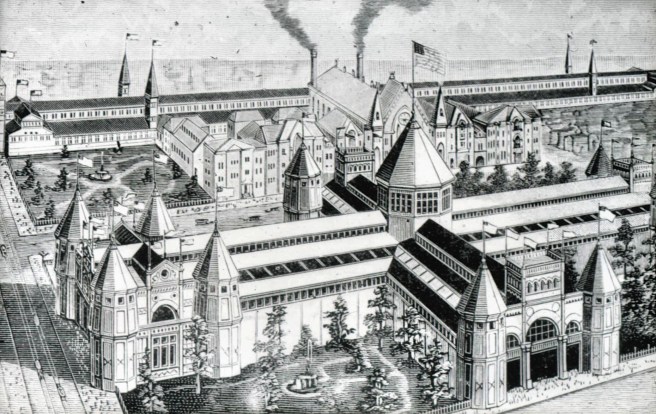

But six acres was chump change compared to how Cincinnati responded to the challenge. 1888 would be Cincinnati’s centennial, having been founded in 1788 (Chicago was only 55 years young in 1888). The city had planned an expanded version of its annual Ohio Valley Expositions for that year (July 4 – October 27) as an appropriate celebration (and as a lure for either convention). Music Hall with its two exhibition wings would still be the nucleus of the 47 acres of landscaped fairgrounds, that were to be expanded with the erection of two temporary buildings.

The large main exhibition, Park Hall, erected across Elm Street from Music Hall in Washington Park had a two-storied cruciform plan, one arm being 600’ x 110’ while the smaller arm’s plan was 400’ x 110’ with their intersection covered with a dome that offered a public observatory. (Park Hall alone was larger than the St. Louis structure.)

Meanwhile, at the rear of Music Hall, what became the public’s favorite attraction, a gargantuan 1300’ long by 150’ wide Machinery Hall spanned the Erie & Miami Canal. It was designed by James McLaughlin (i.e., Shillito’s and the Cincinnati Art Museum) to be a Venetian delight. Four bridges, inspired by Venice spanned the canal within the building, where gondolas and their gondoliers, imported from Venice poled their boats up and down the canal that summer, including a daily parade of decorated barges, attempting to give Americans a taste of what the Italian city proffered, (and offering a tempting invitation to both political parties).

Between the two new buildings, there was more than 950,000 sq. ft. (21.5 acres) of exhibition space located within the 47 acres of landscaped grounds and this didn’t include Music Hall. As had St. Louis done, the Cincinnati fair buildings and the grounds were lit day and night with gas and electricity, in all colors. Fifteen states and three foreign countries presented a variety of delights for visitors. Unfortunately for Cincinnati, neither party took the bait, and the Centennial Exposition was to be the city’s swan song, as Chicago’s Auditorium was rapidly nearing completion.

2.14. PREPARING FOR THE 1888 REPUBLICAN CONVENTION

Looking back at these two projects, Peck’s urgency to push forward with his plan to build the Auditorium makes more sense, especially before the Haymarket bombing. When he had first posed the project in front of the audience on the last night of the 1885 Opera Festival, the St. Louis Hall was nearing completion and plans for the Cincinnati Centennial had to have been under discussion. Peck could project forward three years and see Chicago falling woefully behind the convention/music facilities of its two regional competitors. But he could convince none of his civic-minded (and “frugal”) associates to financially back his project for over a year, that is, until the bombing and its aftermath had brought his equals to their collective senses.

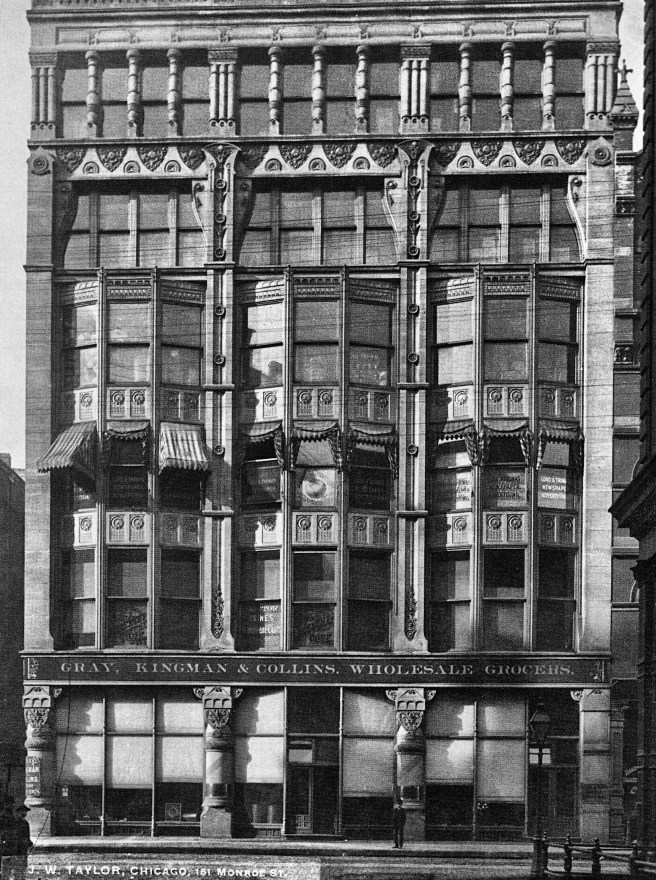

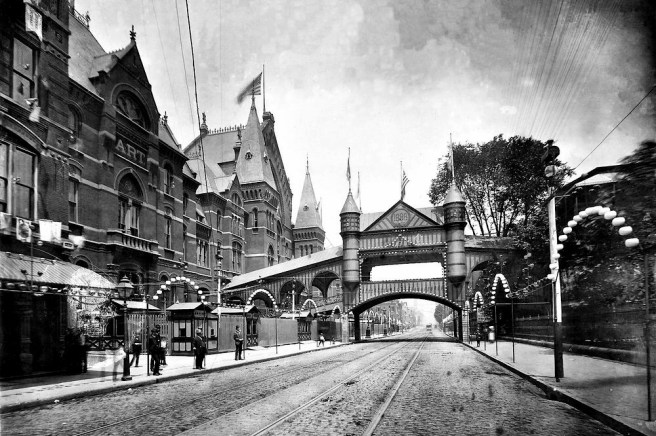

The month following the cornerstone laying saw a hardening of the positions of both the master masons and the unions following the execution of four of the Haymarket defendants on November 11, 1887, that propelled both political parties into the Presidential election of 1888. Peck was hoping for a repeat of the 1884 nominating conventions, that both took place in Chicago’s Exposition Building, which would secure his vision for the Auditorium. The Inter-Ocean stated Chicago’s case in its usual, “detached” manner:

“Cincinnati is bidding high for the National conventions in 1888. This is not discreditable to Cincinnati, but it constitutes no good reason why the conventions should be held there. Cincinnati has been tested. The 1880 Democratic convention was a trying mouthful, and Cincinnati surely remembers the wry faces the gentlemen from the South made over it. Courtesy would require Cincinnati to wait until she is asked for the second test; but already she is urging the Democrats to try again what they clearly enough sickened over before. In the meantime the Democrats have been to Chicago, and are eager to come again… So far as the Republicans convention is concerned Chicago will be favored by the friends of the leading candidates, because to come to cosmopolitan Chicago is to escape from sectional or State bias and to meet under conditions fair to all… The moral to all this is that Chicago ought to have both the National conventions in 1888.”

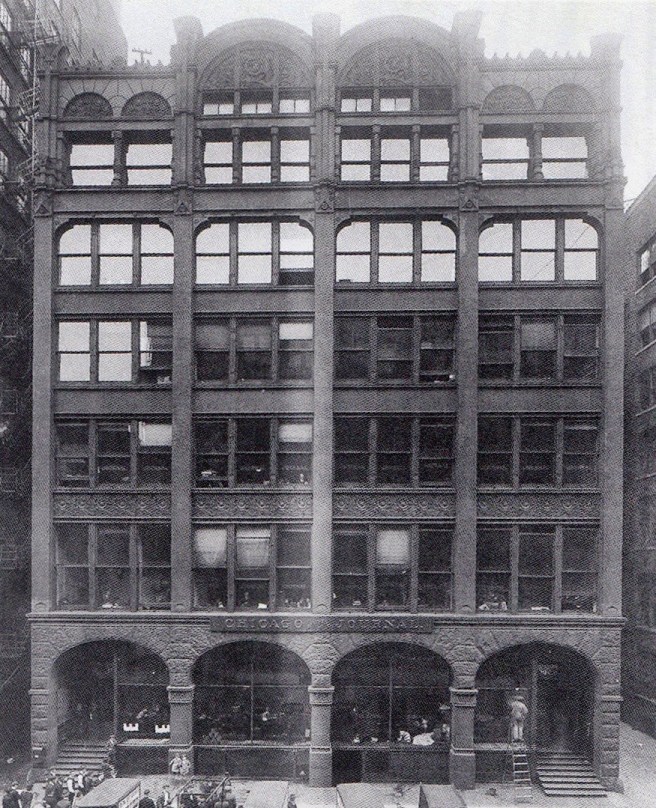

Both parties initially were favorable to such a plan, with the Republicans committing first in December, to hold their convention on June 19-25. Peck was hoping that this would force the Democrats to return to Chicago, especially as it had been the site of the start of Cleveland’s successful campaign. But the United Carpenters Council of Chicago would have none of it, and notified the Democratic National Committee “that the consolidated building trades of the United States would refuse to support any man who was nominated in the Auditorium Building… and a political boycott would be declared that would cost the offending party 250,000 votes.” The Democrats chose St. Louis for their convention, held first between June 5-7, and still Cleveland lost the election, but the Auditorium would never host a Democratic Presidential Convention, to the utter dismay of Peck.

FURTHER READING:

Siry, Joseph M. The Chicago Auditorium Building. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)