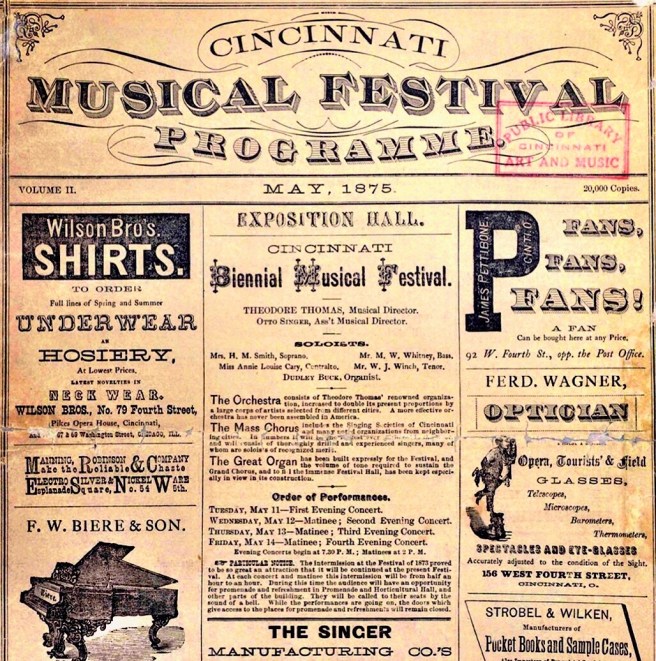

The Second Cincinnati May Festival had been held in May 1875 to standing ovations, with one small glitch:

“At the second concert Mendelssohn’s Elijah was given and during the performance an impressive and characteristic incident happened. There had been a long drought and the country was suffering very much for rain. All day the longed-for clouds had been gathering and just as Thomas gave the signal for the famous chorus, “Thanks be to God,” the rain descended in torrents. Nothing inspired Thomas so quickly as a display of the forces of nature, and, entering instantly into sympathy with the storm, and the feeling of public thankfulness for the coming of the rain, he gathered all his forces – chorus, orchestra, and organ – in one sublime outburst, harmonizing with and rising above the tumult of the elements without, as they sang that great song of thanksgiving: “Thanks be to God, He laveth the thirsty land! The waters gather together, they rush along, they are lifting their voices! The stormy billows are high, their fury is mighty, but the Lord is above them and he is ALMIGHTY!” So tremendous and overpowering was the effect, that to this day, the old members of the chorus of that memorable evening – now thirty-six years in the past – cannot speak of it without tears in their eyes.”

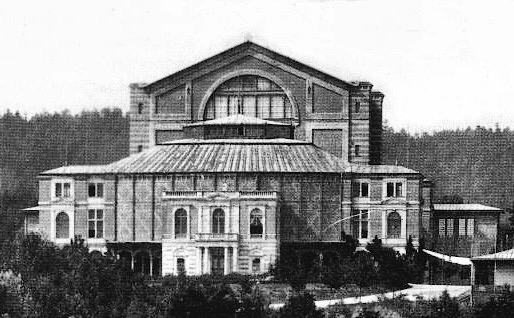

While Thomas had been inspired by the storm, the ferocious noise on the Saengerfest-Halle’s tin roof made by the rain was most embarrassing to the civic pride of Cincinnati’s leading philanthropist, Rueben Springer. Most likely inspired by the Paris Opera House that had opened only five months earlier, and/or Richard Wagner’s Festspielhaus then under construction in Bayreuth, he responded by mounting a campaign to replace the temporary hall with a world-class facility for music, expositions, and conventions. Springer offered to donate $175,000 toward the cost of the project, providing that Cincinnati’s citizens would donate an equal amount. Eventually Springer would pour over $235,000 of his own money to cover the building’s final cost of $500,000. (It is tempting to compare Springer’s actions with those of Chicagoan Uranus B. Crosby, some ten years earlier. While they both intended to upgrade their city’s cultural facilities, Crosby had tried to do it all by himself, and had failed. One wonders if Springer had learned from Crosby’s pioneering attempt and made sure to broaden his campaign into a citywide effort. Nonetheless, Crosby’s ultimate investment of over $600,000 is simply staggering in comparison to what Springer contributed, yet even Springer’s amount would still dwarf the amount pledged by any of his Chicago contemporaries over the next decade. The lack of any Chicagoan willing to “step up” in a manner similar to Springer would simply prevent Chicago from keeping pace with Cincinnati in the culture battle over the next decade.)

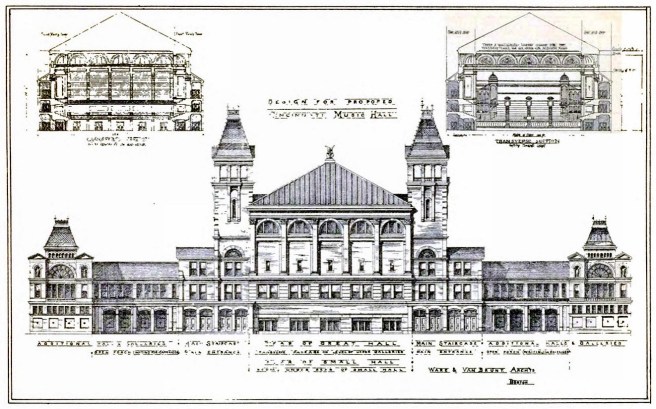

Early in 1876, four local architectural firms submitted designs for the project, but It was soon realized that no one in the city had any expertise in acoustics, so the Boston firm of Ware and Van Brunt, the designers of Boston’s Music Hall, was solicited for a design. In additions to their drawings, Ware and Van Brunt shared a list of seven principles of acoustics in the June 17, 1876, issue of American Architect that gives a snapshot of where the profession was at the time with regards to the design of sound:

“In the scheme here presented, it has been attempted to embody the various precautions that science has suggested, or experience approved, in regard to the acoustic properties of buildings, in the belief that, though it is not at present practicable to make sure that a building shall be exceptionally good in this respect, it is possible to make sure that it shall not be bad.”

Local architects Samuel Hannaford and Henry Proctor were commissioned in the Spring of 1876 to design an auditorium with a capacity of 6500, including the orchestra and the May Festival Chorus. Hannaford, the better known of the two partners, had been born in Devonshire, England from where his family immigrated to Cincinnati when he was nine. He graduated from Cincinnati’s Farmer’s College where he studied architecture and in 1857 began his own firm.

(Cincinnati had at least two of America’s early programs that taught architecture. Hannaford had graduated from the Farmer’s College, founded in 1846 and located in the suburb of College Hill. The city’s other program was in the Ohio Mechanics Institute, founded in 1828, and is known to have been teaching architecture prior to the start of the Civil War. Its most famous graduate from this era was Leroy Buffington who graduated in 1869. We will run into him in 1887 in Minneapolis where he designed the first 28-story skyscraper. My larger point in this side note is that while MIT is usually credited as having founded the first college program in architecture in 1865, by William Ware no less, architecture was already being taught in Cincinnati before the Civil War. This topic needs more research.)

Hannaford revised his plans in accordance with the acoustic ideas contained in the Eastern designs, was given the commission in the spring of 1876 and was asked to have the project completed in time for the 1878 May Festival. The biennial festival had been pushed back one year because construction had to wait until the 1876 Republican National Convention, meeting in Saengerfest-Halle, had nominated Ohio’s favorite son, Rutherford B. Hayes on June 16, 1876. He would defeat Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, Chicago’s William Ogden’s dear friend and longtime lawyer who was nominated in St. Louis, in the highly controversial election that was not resolved until March 2, 1877, only two days before the Inauguration was to take place. (As a side note, Ogden died five months later in his home in Highbridge, Bronx.)

Hannaford and Proctor were inspired by more than just Ware and Van Brunt’s acoustics, apparently, when I juxtapose their design of their recently-completed Harvard’s Memorial Hall (1870-7) with Hannaford’s entrance façade. If one looks closely, Hannaford even copied, for all practical purposes, the geometric mullions of its central rose window.

And so, in the depth of the great depression of the 1870s, while the rest of the country struggled to make ends meet, Cincinnati, the “Paris of America,” had plowed ahead with its plan to become the nation’s Cultural and Convention Center. The city’s economy had remained relatively strong, compared to the rest of the country due to the fact that Cincinnati had been founded in 1788. This was too early to be financed with any significant East Coast venture capital, and therefore, had evolved its financial and industrial base independent of any reliance on New York or Boston. (This may be best evidenced in the fact that during both the Depressions of 1873-9 and 1929-WW2, not one Cincinnati bank closed.)

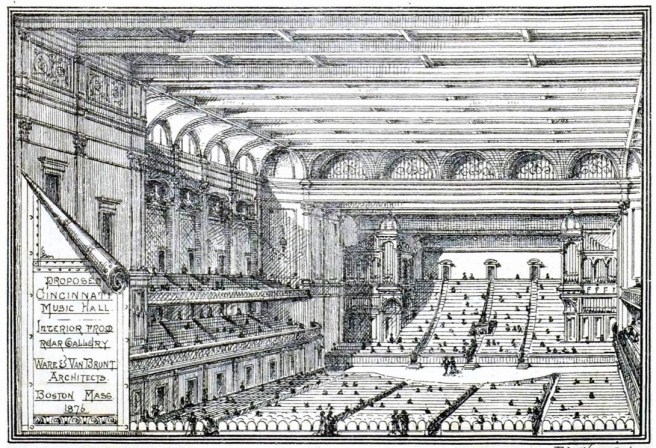

Construction commenced in October 1876 on Hannaford’s final design that incorporated an auditorium with a capacity of 5,228, the largest in the country. The house could seat 4428, while the stage was large enough to accommodate the Festival’s chorus of 700 and Thomas’ orchestra of 100. The most dramatic departure in the design of the interior was the almost complete elimination of all private boxes. Because the house also had to function as a multipurpose hall, Hannaford eliminated the tiers of private boxes found in European Opera Houses In favor of public first and second balconies.

The only private boxes were quietly slipped under the first balcony located at either side.

A Recital Hall for chamber groups was also provided, located on the third floor, directly over the main entrance vestibule. Hannaford’s exterior revealed the influence of the latest thinking in European Opera Houses, in that it incorporated a monumental gabled flyspace, similar to that of the Paris Opera House that had opened only a year and a half earlier and Richard Wagner’s Bayreuth Festspielhaus, that had just opened to the public some two months earlier on August 13 with a performance of Das Rheingold.

The exterior design is obviously high Victorian Gothic, with a red brick body with superbly detailed ornamental patterns, that easily could have been inspired by Furness’ work in Philadelphia. (Online)

FURTHER READING:

Miller, Zane L., and George F. Roth. Cincinnati’s Music Hall. Virginia Beach: Jordan, 1978.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)