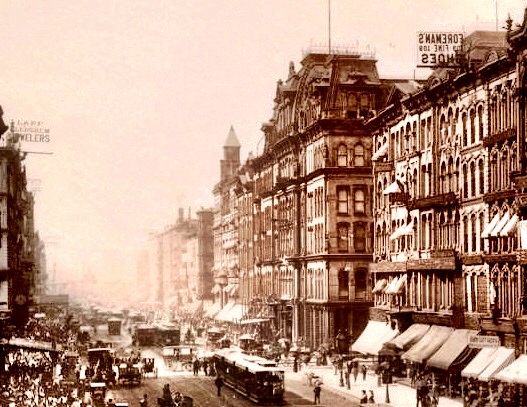

If having to replace the interior structure of its wholesale store wasn’t enough, Field & Leiter’s retail store on State Street caught fire on November 14, 1877. (See Sec. 1.6) The fire was a grim reminder that even six years after the 1871 fire not much had changed in Chicago’s construction for the better. The five-story Singer Building designed by E.S. Jennison in 1872 that housed its retail operations caught fire in its wooden double-roof. Jennison had designed a six-story Second Empire palace, including mansard roof, but at the last moment Field and Leiter cancelled the construction of the mansard (as was done in a number of post-fire buildings, such as the Kendall Block). The sixth floor structure had already been erected and it was decided to simply construct a sloping flat wood roof, covered with tin over the wood-planked sixth floor. The cavity between these two wooden surfaces varied in depth from 6′ to a few inches, a firefighter’s nightmare just waiting to happen.

Once again, the building had been typical for the post-fire period in that while it was well protected on the outside and roof, the interior structure consisted of cast iron columns and plaster-covered timber beams. The building, in fact, was better protected than most, with two iron water tanks under the roof that fed standpipes located throughout the building. Unfortunately, this happened to be one of the major problems in the fire, that apparently started in the space in between the roof and the cover sixth floor, because one of the tanks that was sitting on the timber beams, gave way and crushed through the wooden stairs to the basement, killing six firemen and injuring several more. The spread of the fire downward was facilitated by three open-shaft elevators within the building. From the historical record, it appears that Field & Leiter during its first ten years of business was not as lucky with its buildings as it was with its business. Similar to how they reacted to the 1871 fire, Field & Leiter had swiftly managed to find temporary space, this time in the Exposition Building on Michigan Avenue as its interim home, opening for business in two weeks’ time on November 27.

Characteristically, City Council showed little concern over the problem. Instead of addressing the danger of the continued use of wooden Mansard roofs, Council passed an ordinance that required:

“All buildings except such as are used for private residences exclusively, of four or more stories in height, shall be provided with one or more metallic ladders or metallic fire escapes extending from the sidewalk to the upper stories of such buildings and on the outer walls thereof.”

Once again, it was the Insurance Companies that made a positive attempt to improve construction. On January 16, 1878 Alfred Wright, the Secretary of the Chicago Board of Underwriters, issued the following:

“In view of the disasters which have resulted from the location of water-tanks in the upper stories of buildings where fires have occurred, and with the conviction that similar or still more calamitous consequences are likely to follow where such destructive agencies are permitted to exist, this board is forced to insist upon the observance of the following stipulations in their construction and arrangement: All water tanks, if constructed of wood, must be open at the top; if of metal or of other material than wood, they shall rest upon a foundation of brick, or some walls of solid masonry, or upon heavy iron girders, both ends of which shall rest upon solid brick or stone walls. On all buildings (with their contents) having water-tanks not constructed in conformity with above standard, a charge of not less than 10 cents per $100 will be added to the basic rate. This action shall take effect from this day; but on any building now provided with tanks not conforming to above requirements, if altered and constructed in compliance therewith before March 1, 1878, this charge of 10 cents will be rebated.”

However, the Singer Building’s fire may have been a blessing in disguise. A post-fire investigation discovered that of the wooden members that had survived, most were dry-rotted almost to the point of collapse, not an unusual problem in this period, as was discussed in the previous post. It had been originally planned to repair the upper two floors gutted by the fire, but with the finding of dry-rot, the entire interior was demolished. Singer commissioned New York architect James Van Dyke to redesign the building using the surviving walls and requiring the addition of the mansarded sixth floor, ostensibly to make a building for Field & Leiter that would be as tall as Shillito’s new store in Cincinnati. The internal structure was completely framed in iron, fireproofed with non-combustible materials. One would assume that these were the products of Wight and Loring. The American Architect’s “Chicago Correspondent” was quick to report on the incorporation of a complete iron structure in the new Singer Building:

“The prospect of its (iron framing) extensive use in the future, coupled with the recent discovery of its weakness as a fire-resister, points with greater force than ever to the importance of adopting safe methods of constructing fire-resisting ceilings under the beams.”

Field and Leiter had agreed amongst themselves that they would buy the building and the corner lot from Singer for $500,000, but Singer was asking $700,000. Field was in New York at a critical point in the negotiations when Singer broached the higher price to Leiter who, known for his quick temper, refused the offer. Singer immediately turned around and offered the building to their competitors, Carson, Pirie, Scott for an annual lease of $70,000 that they took on the spot. Singer had snookered them and they knew it. Not wanting to lose the prized corner on State Street, the two partners belatedly bought the building for the original $700,000 with their personal funds and leased it back to the company. They also had to throw in an extra $100,000 to compensate Carson’s for cancelling its lease. Marshall Field had a long memory…

FURTHER READING:

Twyman, Robert W. History of Marshall Field & Co. 1852-1906. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1954.

I’d like to thank Brian Kelly of “brianbrands.com” for offering his knowledge of the Field/Leiter relationship.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)

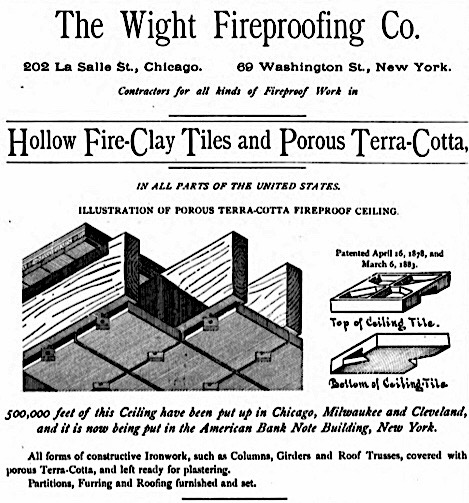

3.12. WIGHT FIREPROTECTS WOOD FLOORS

The “Chicago Correspondent” continued to champion the search for better fireproofed-iron construction. Only a month later he wrote:

“As in 1872, with the experience of a great disaster before us, the thoughts of many were turned towards providing against the contingency of its recurrence, so now, with the news coming in from every quarter, of death-dealing and property-destroying conflagrations, the subject is being agitated in Chicago and the west with renewed vigor….But beyond the erection of thick walls but few improvements calculated to guard against fire have been adopted until recently. Several buildings with iron floor-beams, which were supposed to be fire-proof, were erected after the great fire; but none of them show any advances upon heretofore well-known methods which are now known to be anything but fire-proof, for the particular reason that the necessity for protecting the constructive iron-work has not been recognized.”

As the 1874 fire had motivated Wight to investigate the protection of iron columns and correspondingly invent his system of wood and later terra cotta encased columns, so it seems that the Singer Building fire had moved Wight to solve the problem of fireproofing wooden floors. While he was writing the last two articles, Wight was busy at work perfecting a system of terra cotta ceiling tiles for fireproofing either wood or iron floor structures. What seems odd to me, however, is that by this date nowhere is there any evidence that prior to 1880 that Wight had any interest in using the flat segmental tile arch system for floors patented by Johnson back in 1871. In essence, the “Chicago Correspondent” was creating an awareness of the problem and a corresponding need for Wight’s new system of ceiling tiles that was patented on April 16, 1878, only three weeks after the publication of the second article. (Note that in 1878, seven years after the 1871 fire, Chicago was still building commercial buildings with wood floor joists!)

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)