The third of the large buildings granted a building permit during the first week March 1884 was the Home Insurance Building. The project was initiated by developer Edward C. Waller, who had been a close friend of Daniel Burnham’s ever since the two of them had traveled to Nevada in search of silver in 1869. While Burnham had chosen the path of architecture as an adult, Waller had gravitated to real estate development and had gained a reputation as a major player in downtown properties. Waller had assembled the lots on the northeast corner of Adams and La Salle, opposite the “temporary” city hall or “Rookery” during 1883 for the British-owned insurance company to erect a new office building. The company apparently had initiated a design competition in February 1884 for a building adjacent to the Calumet Building and diagonally opposite from the Insurance Exchange.

Managing the competition was the company’s Chicago agent, Arthur C. Ducat. Ducat was an Irish immigrant who at the age of 21 had settled in Chicago during 1851, finding employment in engineering and as insurance agent, developing a keen interest in finding better methods of fire protection for buildings. He had fought in the Civil War, raising to the rank of Lt. Colonel before his service had ended in late Oct. 1862. He had then gone on to serve as the Inspector General in the West, when he more than likely made the acquaintance of Maj. William Le Baron Jenney. After the end of the War, Ducat returned to Chicago becoming the agent for the Home Insurance Company, and also a Maj. General in charge of the Illinois National Guard.

By the time of this competition, Jenney had fallen into the role of the elder statesman among Chicago’s architects. His practice had fallen from its heyday during the post-fire reconstruction, to the point where he had not designed a major building (the miniscule five-story First Leiter Building notwithstanding) in the intervening ten-year period since the Portland Block and the Lakeside Building of 1873, that, coincidentally, was located diagonally to the east across Adams Street from the site. Instead, Jenney had become a man of letters: teaching architecture briefly at the University of Michigan in 1876 during the depth of the Depression, handling correspondence for the A.I.A., and lecturing on architectural history at the Art Institute. While these pursuits were respectable, they were hardly in the same league with the contemporary trail-blazing activities of the big building designers Boyington, Beman, and Burnham & Root. The true measure of the professional stature of Jenney’s office in the early 1880s was best exemplified in Peter C. Brooks’ decision, who owned Jenney’s Portland Block, to hire Burnham & Root, and not Jenney, to design the Montauk Block, Chicago’s first skyscraper.

Had Jenney not been a good friend of Ducat, it is reasonable to assume that Jenney’s career would have faded into obscurity. Instead, Jenney recalled later in life that Ducat had given him the chance to design his first tall office building: “In 1883 [sic-it was in 1884], when the Home Insurance Company proposed to erect a building in Chicago, Ducat (who was the leading agent in the West) kindly recommended me to be their architect.” The first report of the competition was in late February 1884, that correlates with the first mention of the Home Insurance Building in Jenney’s personal notes, dated February 19. The building at this date was to be only six stories plus a basement:

“The basement story to be one step up from the sidewalk, similar to the Boreel Building… This would make the building 84′-5″ high [six stories plus basement], if another, [it] would be 96′, which is high enough and I would object to it being any higher… The basement to be of some suitable stone to be decided upon. The rest of the building to be of brick with terra cotta or molded brick trimmings.”

When the building committee from New York arrived in Chicago during the first week in March to review the competition drawings for the new building, that were reported to have been submissions by three different architects, it apparently had already increased the height of the building because the permit obtained on March 1, was for an eight-story plus basement structure. Suspiciously, it was reported that even though a winner had not yet been chosen (Jenney would be officially chosen two weeks later), the permit was taken out upon the plans of Jenney, and that he, upon the orders of the company (and undoubtedly at the encouragement of Jenney’s friend, Ducat), had already begun to let the contracts for the cut stone and other materials.

The following month, Inland Architect reported that Jenney’s design had indeed been chosen the winner from plans submitted by a half dozen of Chicago’s best architects. The design continued to be refined during the spring of 1884; the final height was set on April 28, 1884, at 150′ with nine stories plus basement. In plan, Jenney first placed single-loaded corridors along both street fronts. The remaining two lotlines were protected by code-required masonry bearing walls. The lot was sufficiently wide for Jenney to “slip-in” two offices in back of the Adams slab turning it into a double-loaded corridor. This required the elevator core to be pushed deep enough into the lot to make a lightwell that also allowed one office to be located on the opposite side of the lightwell.

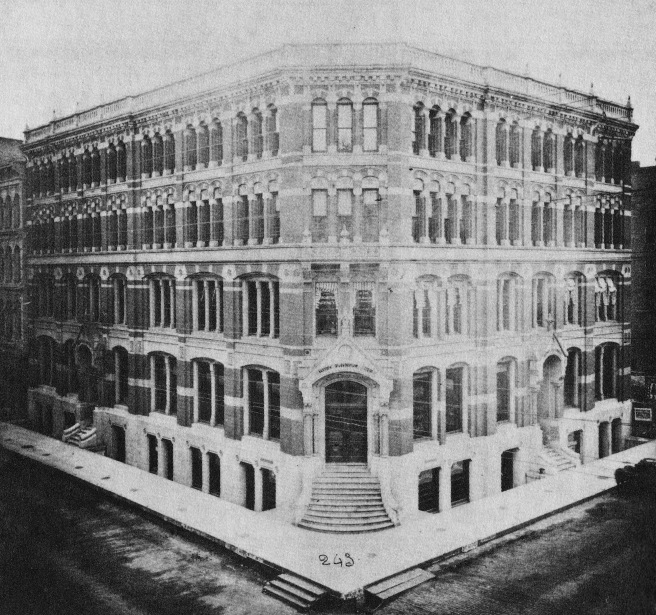

As was the case in the design of the Portland Block and the First Leiter Building, Jenney’s primary concern in the design of the building’s elevations was to maximize daylighting of the interior. He chose the pier-and-spandrel language of the Leiter Building for seven of the ten floors, retaining the use of the arch to emphasize the termination of the base layer in the second floor and the termination of the building in the tenth floor. As he had done in the Portland Block and the First Leiter Building, he also layered the elevation with his characteristic contrasting light stone banding at every floor level. The horizontal accent of the building allowed the design to gracefully accept the anticipated addition of extra floors at a later date.

The obvious lack of clarity in his design of its elevations is straightforwardly explained as this was his first attempt at designing the elevation of a tall building. He began where most Chicago architects had started (Cobb & Frost being the exception) with a stone base. Quite correctly, he improved upon Root’s adjacent Insurance Exchange by making the stone base two stories tall that gracefully accepted the triumphal-arched entry. He also took Root’s balcony located over the entrance at the fourth floor but did it one better: he made a second balcony overlooking the triumphal arch, and just for good measure, inserted a third, albeit subordinate balcony in between these, creating a threesome of balconies.

Where Jenney got into trouble was in the eight-storied brick body in which instead of treating each floor alike as he had done with the First Leiter, Jenney followed the current fashion of grouping floors together into larger layers with colossal pilasters. Jenney followed Root’s Insurance Exchange and Boyington’s Royal Insurance Building by placing pilasters at the corners and at the location of the entrance on both street fronts. He used the pilasters to create a sequence of base:2:3:2:1 that was very similar to Post’s Mills Building in New York.

Jenney’s detailing of double windows also echoed the Mills Building as well as the Royal Insurance Building. The top floor again revealed the influence of the Royal Insurance’s Quincy facade in the semicircular arched windows that Jenney had originally rendered to have been sculpted panels as Boyington had detailed.

Jenney’s larger horizontally-grouped layers were reinforced with continuous stone cornices. This, in and of itself would have been fine, except for those incessant horizontal bands of light stone at each floor. The resulting composition of the multi-storied layers was simply unresolved, for the continuous vertical piers not only clashed with, but were visually overshadowed by the highly-contrasting stone horizontal bands. The most awkward of all the detailing in the building, however, occurred in the pilasters in the middle, three-story layer, where Jenney naively allowed the subordinate stone banding to harshly continue through the would-be dominant brick pilasters at floors 6 and 7, creating a pair of unbroken horizontal lines around the building that resulted in a cacophony of architectural forces.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)