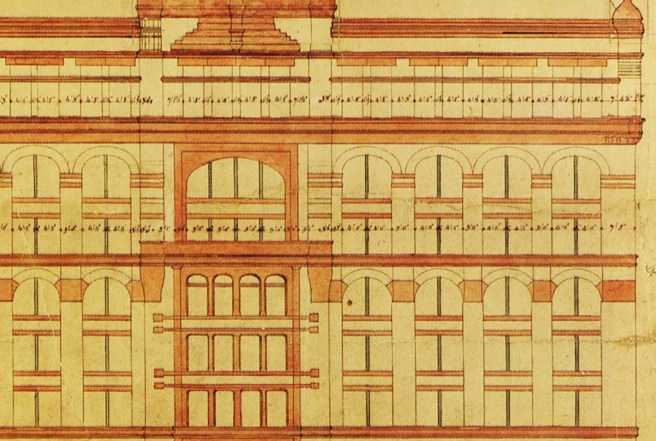

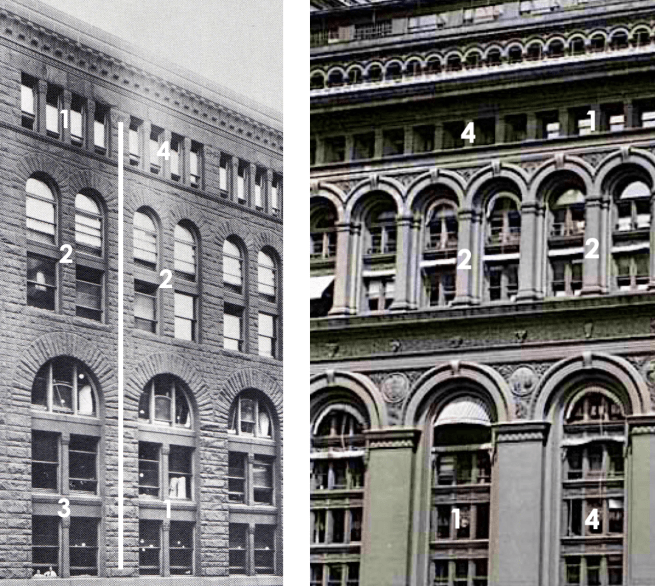

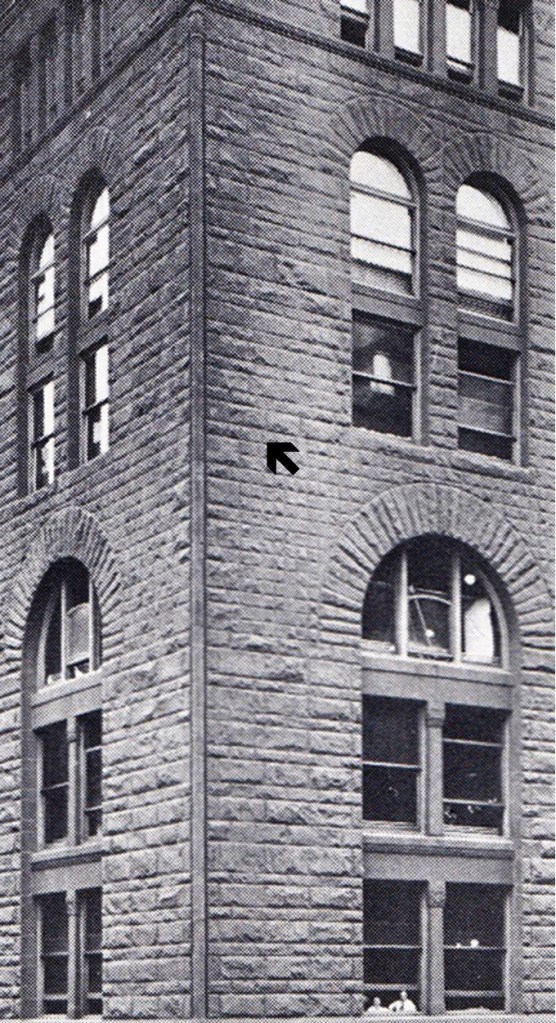

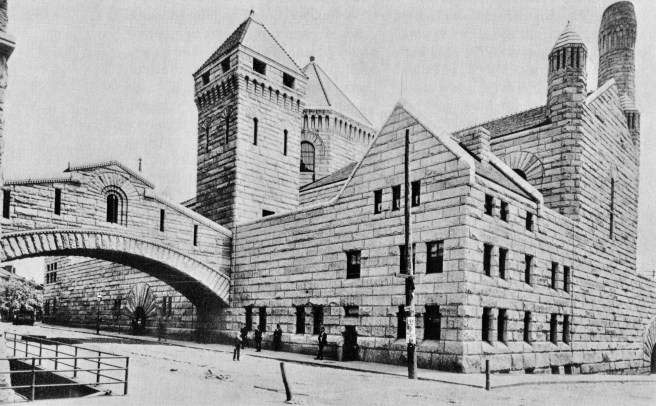

These two great architects had learned some “new tricks” from each other’s buildings. Root had had an immediate impact on Richardson’s work. This was first seen in Richardson’s desire to design the Field Store as a red brick box, inspired by Root’s Burlington Building standing across the street from the Field Store, rather than using his characteristic stone walls topped with a high-profile roof. Although Field denied him this opportunity, Richardson succeeded in realizing the red brick box in his next (and last) two large urban commissions. In December 1885, he was commissioned to design an armory in Detroit as a memorial to John J. Bagley, Michigan’s reform-minded governor who had died from tuberculosis in 1881. The degree of openness that Richardson achieved in the brick streetfront was unknown in his exteriors prior to his trip to Chicago. This was accomplished with a three span arcade that rose for the first three stories. He had employed a three-storied arcade in the courtyard elevation of the Allegheny County Courthouse, but had only opened up the upper-most story as a clerestory for the courtrooms. When Richardson arrived in Chicago he found Root had detailed triple windows under such an arcade in both the McCormick Building and well as the then under-construction Art Institute.

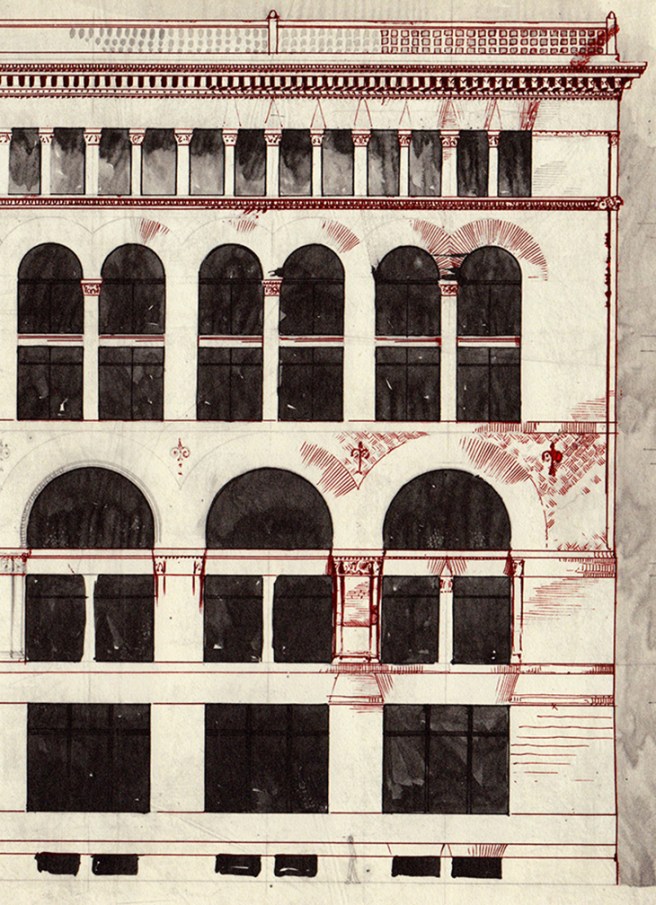

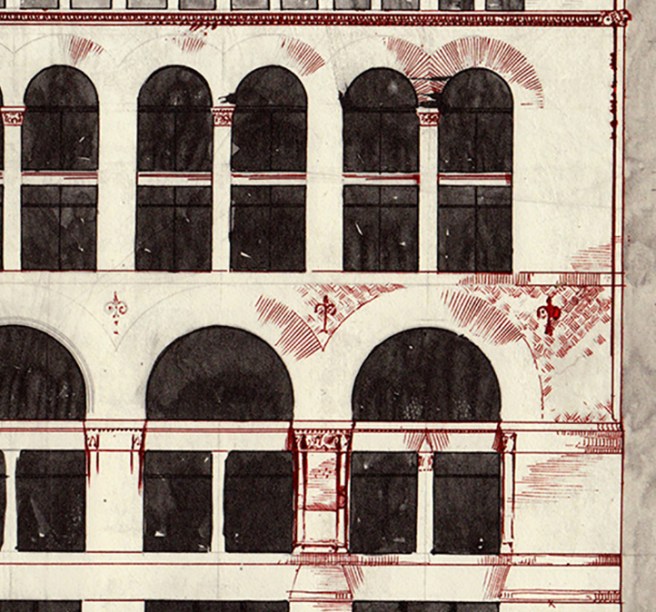

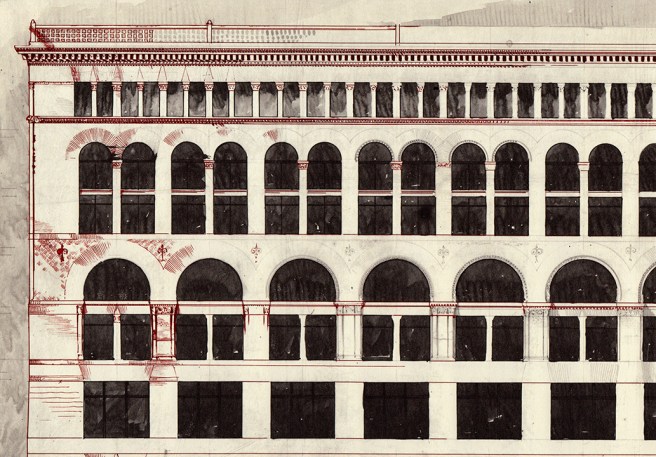

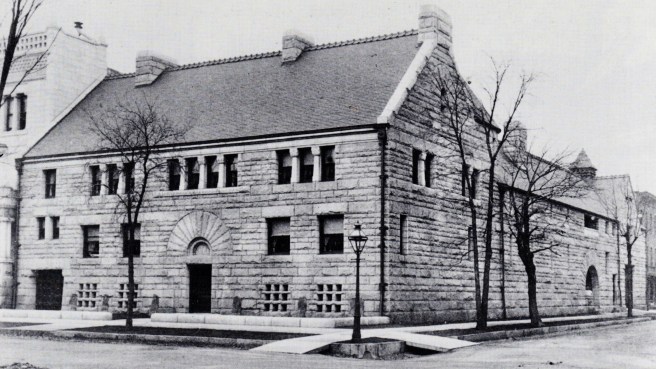

It is easy to read the influence of Root, as well as once again, Peabody & Stearns, in Richardson’s design. The model for the elevation was the McCormick Building with its triple windows within each arch as well as the single, square-headed windows in the attic. From Peabody & Stearns R. H. White store he appropriated the projected arch course that highlighted each of the primary arches. Here we see him taking the idea that he had been evolving since his return from Europe in 1882 that he had incorporated in the Field Store, that is the wall as one, continuous surface. This is especially noticeable in the upper portion of the elevation in which he has cut out the five rectangular windows above each primary arch.

Although Richardson’s characteristic dormers have reappeared, they have been pulled two-thirds into the body of the building, so that they are more of an ornamental vestige of the boldly projected volumes of his past. This placement resulted in an awkward equilibrium between the straight cornice and the triangular peaks of the three gables. This was his final use of the dormer, as if he couldn’t be sure he had made the right decision in the design of the Field Store and wanted one more dance with his old friend, the dormer. He had been right in the Field Store for the gables dated the armory’s design. It was time for Richardson to join his younger peers of the 1880s. His next building would have a flat roof.

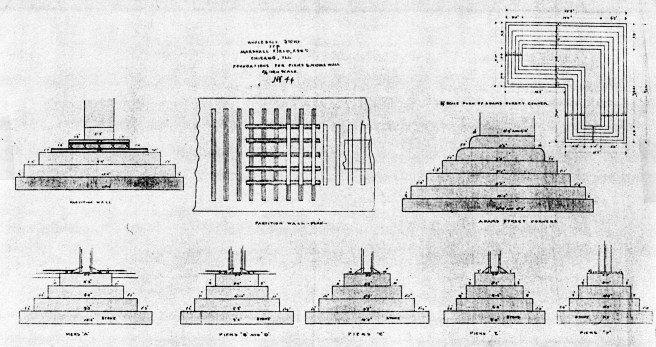

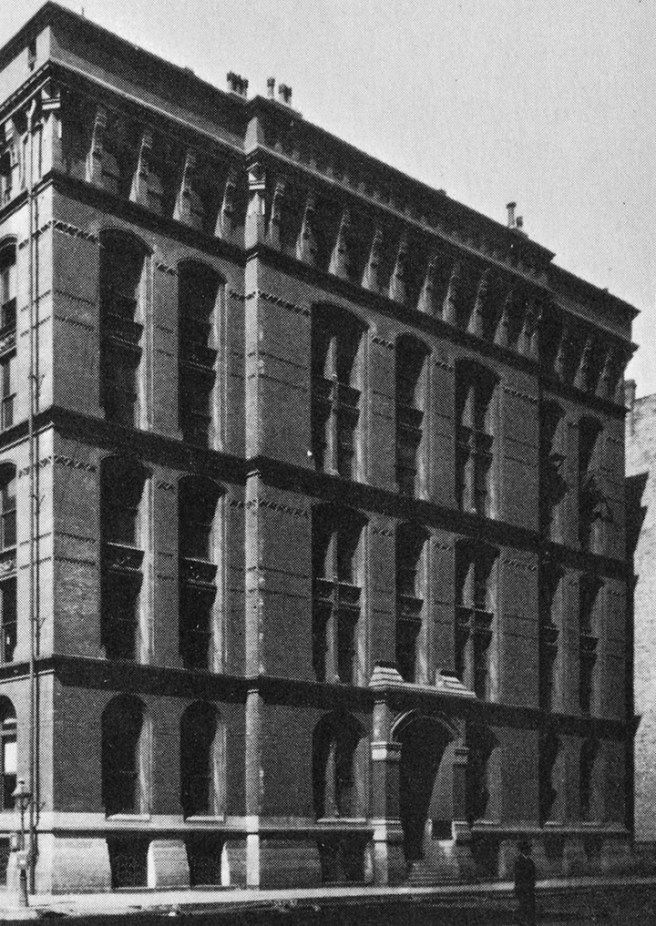

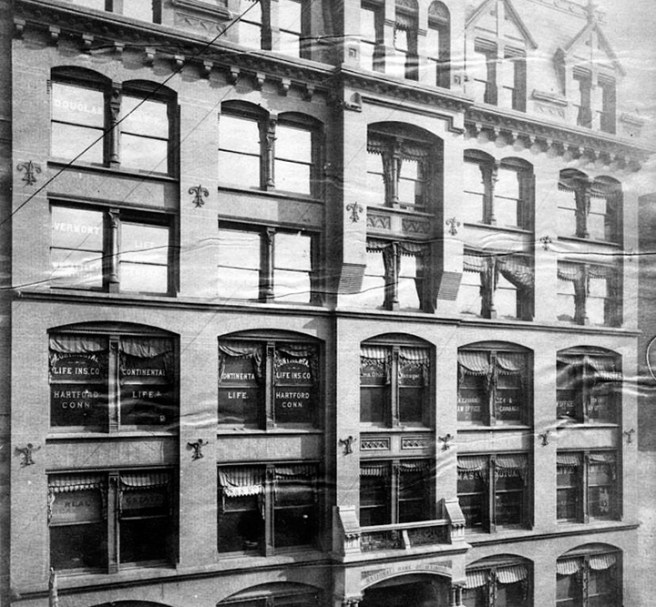

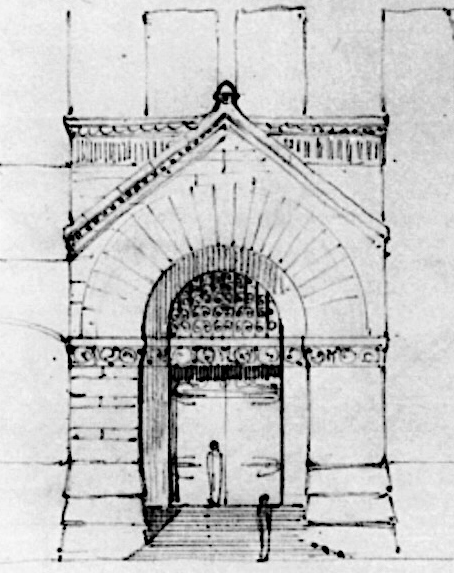

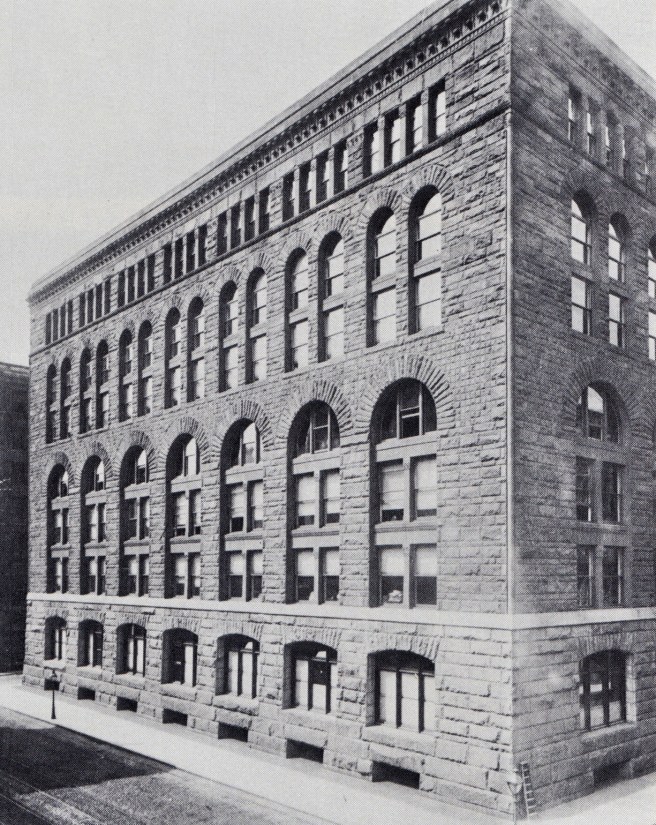

If one doubted the influence of either of these two precedents on Richardson’s last designs, one needed only to wait a few weeks for Richardson to design an even more direct quote. In January 1886, Richardson was commissioned to design a six-story office building in Boston on Harrison Avenue for F. L. Ames. (This building is frequently referred to as the F. L. Ames Store, although only the ground floor was occupied as a store by J. H. Pray, Sons and Company, while the upper five floors contained office space.) Richardson could not ignore the R.H. White Store in this project if for no other reason than it sat directly across the street from where he was to build the new Ames Building.

He began by taking the multistoried arcade from the White Building, including its projected arched silhouettes. He increased the opening under each arch, as he had done in the Detroit façade, by echoing Root’s McCormick Building’s triple windows, as well as the same proportions of its one-story base, a four-story arcade (supported on three-story continuous piers), and a single-story top. In the cornice, he appears to have recalled the machicolated cornice of the Beacon Hill reservoir, except the vertical masonry mullions are not cantilevered over the surface of the wall, but rather, gently flair or taper from being flush with the wall to their final projection.

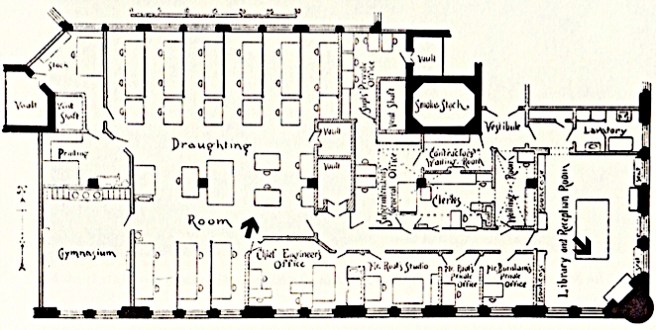

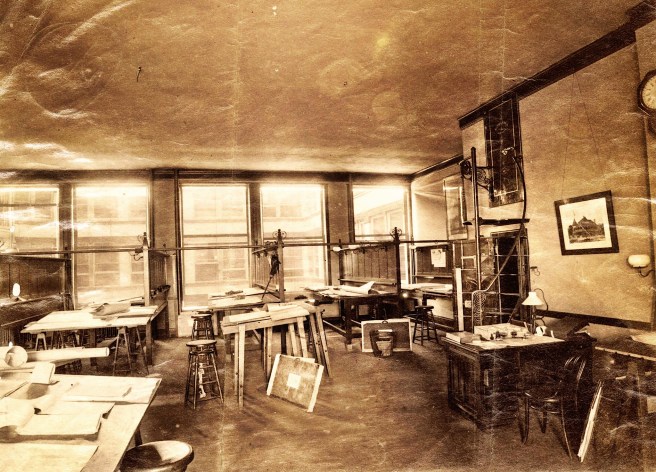

Here I will flag Root’s early designs for the Monadnock Block as a potential source for this detail. At the time that Richardson had visited Root’s office in November 1885, Root was working on the early designs for the 13-story Monadnock Block. Replace Root’s Egyptian capitals with Richardson’s arches, and the result is a shortened sibling of Root’s 1885 vision of the Monadnock Block. Maybe Richardson had been so busy concentrating on Root’s drawings during his visit that he wasn’t able to pay enough attention to Root’s response to his question about the foundations for the Field Store.

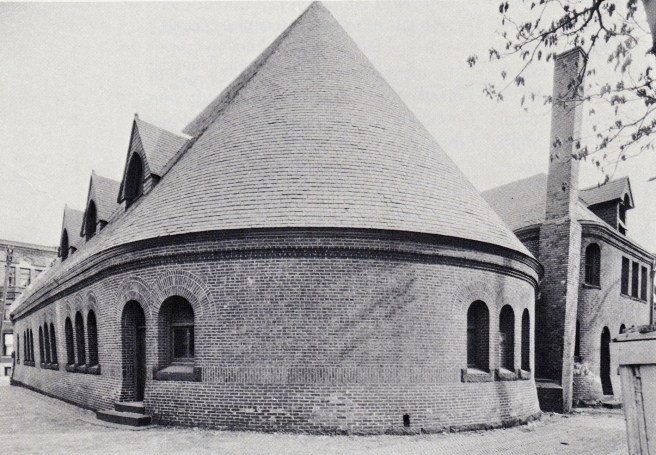

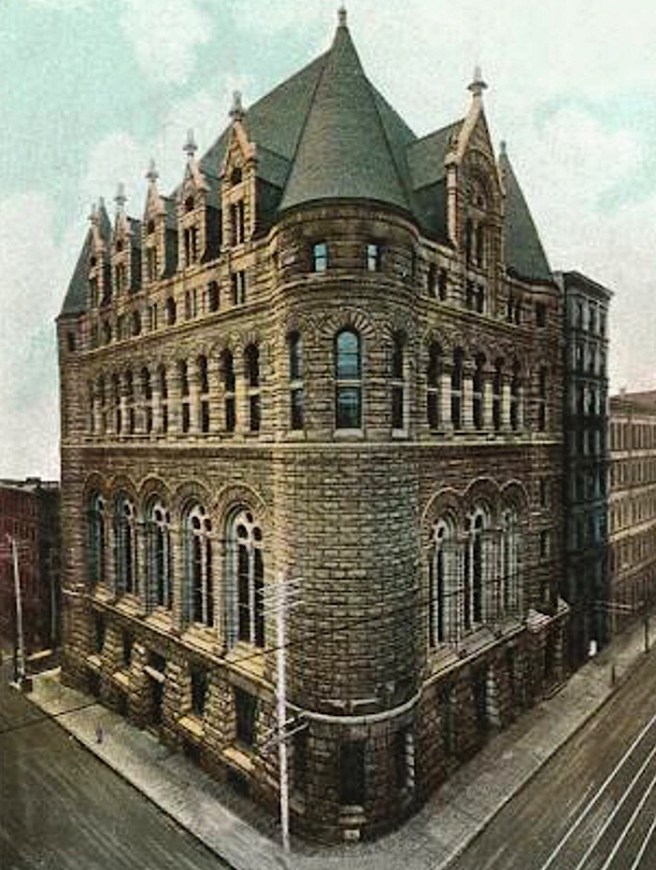

But wait! Richardson did give us a radical design in this building that hasn’t truly been appreciated for its originality. The Ames Building had no corners because Richardson had rounded the building around the two corners of its site! In his designs prior to the Ames, such as the Allegheny County Jail and the Glessner House, I had discussed how his elimination of the layering had allowed the building to be read as a sculptural mass/volume. But these buildings still had sharp, defined corners, so they read as cubic masses. In the Ames Building, Richadrson had simply wrapped his five-story arcade along the entire perimeter of the site, curving the arch of the arcade in plan where the sidewalk curved at the lot’s two intersections. In a sense, this is a complete inversion of the Field Store.

Ever since Labrouste had used an arcade in the elevation of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, architects have had to reinforce the corner of such elevations to buttress the thrusts. In the Ames Building, where one would expect to find another such solid pier, Richardson doesn’t stop the arcade but continues it around the corner! This required that he not only curve the arch over this bay in plan (and to curve the glass windows: it appears he simply used three segments to make the curve) but also to curve this arch in elevation. So think about this detail for a few moments…

First, the keystone of the arch is not in the same plane that is defined by the two spring points of the arch: it is cantilevered beyond its supports, therefore, gravity wants to pull the highpoint of the arch down, meaning that it is rotating away from the plane determined by the two supports. This action is called torsion. Of course, it stood up, but only because the curved arch was tied back into the rest of the building’s structure.

We don’t even find such three-dimensional curvilinearity in the Canopus in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli. Here, while the structure curves in every bay, the curve either is in plan of the lintel or in the elevation of the arch. The arch doesn’t also curve in plan. Second, imagine the Ames Building at night when the interior is lit. The “corner” has no mass. This was a big deal when Walter Gropius cantilevered the floors in the corners in the Fagus Works of 1911! Richardson had scooped Gropius by twenty-five years! (Someone needs to thoroughly research and document the Ames Store.) The idea of a building with no corners would be adopted and developed by Root during the remainder of his career.

Tragically, Richardson would not live to see his last designs constructed, for on April 27, 1886, he finally succumbed to Bright’s disease, a chronic infection that attacks the kidneys that had increasingly afflicted him during the last years of his life. Having completed his masterpiece, the Allegheny County Courthouse, the design for the Field Wholesale Store had signaled a radical shift in his design intentions, a mid-life crisis, if you will. His last two urban projects showed the direction he wanted to take his architecture. Following his return from his 1882 European tour, he had been pursuing the simplification of his designs. First, he had abandoned his characteristic dual-color light stone with dark stone trim in favor of a monochromatic body. Then he had begun to eliminate the horizontal layers in his elevations in favor of achieving a single volumetric sculptural form. With the Field Store he had abandoned his “Medieval crown” in favor of a flat cornice. One can only speculate what he would have been able to accomplish had he lived beyond the forty-seven years granted him. Would he have produced as powerful designs in the new aesthetic as he had built with the picturesque Romanesque, or had the muses been kind to him by relieving him after he had accomplished his destiny? Either way there is no doubt that American Architecture had prematurely lost its first great figure.

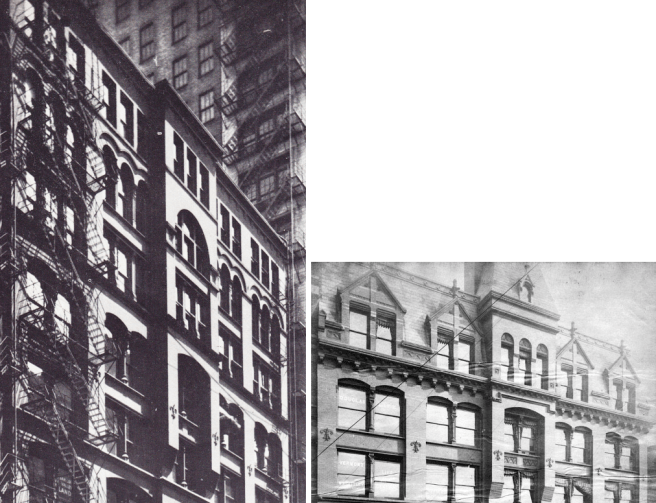

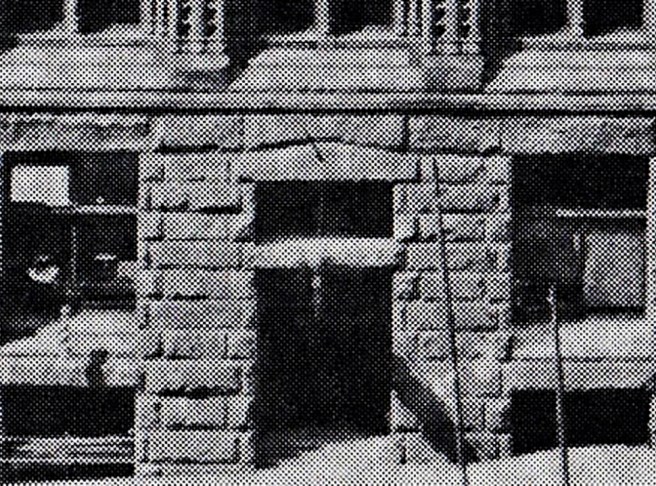

Meanwhile, Root had mutually benefitted from Richardson’s presence in Chicago. Richardson’s elimination of the need to articulate the middle of an elevation into distinct horizontal layers in the Field Store would set Root, and other Chicago architects free to express the middle of their elevations as one continuous volume or entity, bounded by a base at the ground and at the sky with some sort of termination. Root quickly experimented with this idea in two relatively inconsequential residential projects in early 1886. In both the Argyle Apartments at the northwest corner of Michigan and Jackson, and the Pickwick Flats at the southeast corner of Michigan and Twentieth, Root detailed the five middle stories of both buildings as unbroken, flat surfaces of brick that were given a vertical articulation with the regular spacing of bay windows. He had given birth to their subsequent siblings that would incorporate both details and culminate in his final design for the Monadnock Block, that would continue to be delayed for the next three years.

Look carefully at these two apartment buildings: how did Root eliminate the corners, à la Richardson’s Ames Building? Of course, he put a stack of bay windows at the corner, as Richardson had done in the tower of the Allegheny County Courthouse, thereby not only eliminating the corner, but implying that the building had been wrapped with one continuous surface. I could also point to the Maller Building standing diagonally across from the site of the Rookery as a precedent with the exception that J.J. Flanders had detailed this masonry cylinder as a solid.

While a sharp-edged corner allows one to read the two-dimensional plane of the wall, the elimination of the corner emphasized the building’s volume or mass, depending upon how the architect detailed the openings (flush with the surface for volume or setback allowing one to read the thickness/mass of the wall). I reiterate once again, one technique (2-D surface) is not inherently better than the other (3-D volume/mass), but they do impart a different type of “read” to a building, a conscious design decision to be made by the architect.

The two apartment buildings would be Root’s last design for a building in Chicago for the next two and a half years. The deadline for the eight-hour workday that the IWPA, back in October 1884 had set for May 1, 1886, had finally arrived. This timebomb detonated in the evening of May 4 in Chicago’s Haymarket Square. The socio/political climate in the city would change overnight to one that would not be conducive for any capital investment for the upcoming two years (with the eventual exception of the Auditorium, that was erected specifically in response to the city’s boiling class-conflict as Joseph Siry has documented). Meanwhile, Manifest Destiny that brought with it architecture, would continue moving west of the Mississippi River. Kansas City would challenge Chicago’s meat industry (as Chicago had done to Cincinnati), and Minneapolis/St. Paul would surpass Chicago’s wheat business. Both cities will give Chicago’s architects the opportunity to continue the evolution of the skyscraper during the coming dark days in Chicago…

I will be taking a week-long hiatus from the blog. I should return with the start of Volume Four (1886-1891) by Feb. 16. In the meanwhile, I hope you enjoyed my presentation of Chicago’s architecture during the period 1874-1886. If you have the time, I’d appreciate hearing from you about what you have learned so far. I guess it’s the teacher in me…… Thanks for following! In the meanwhile, here’s something to look forward to…

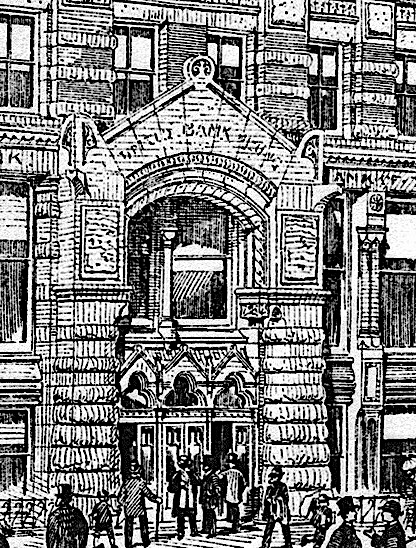

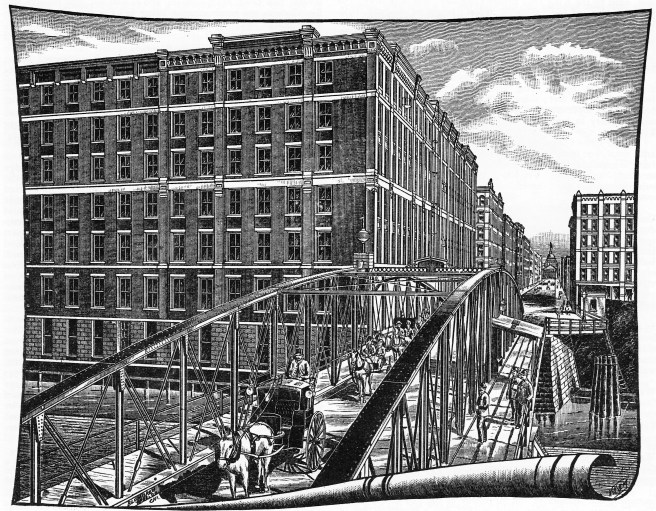

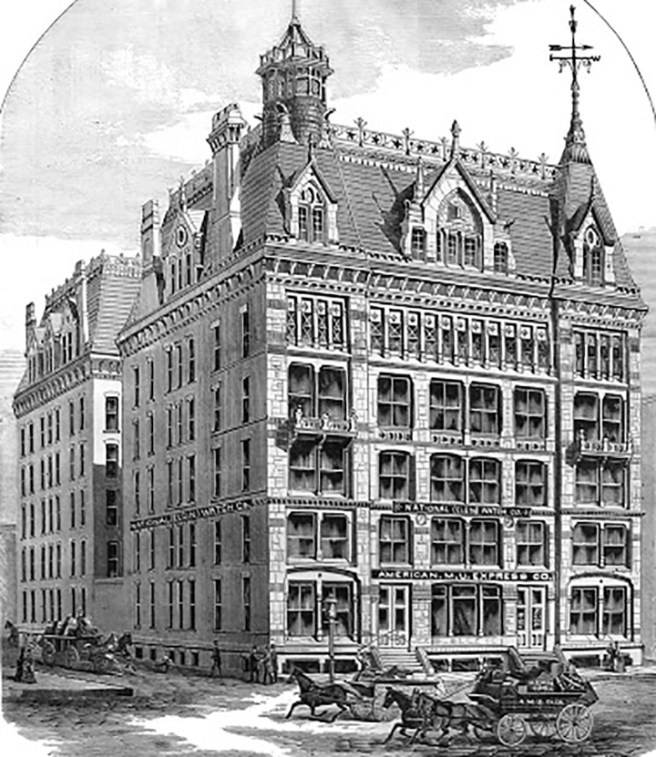

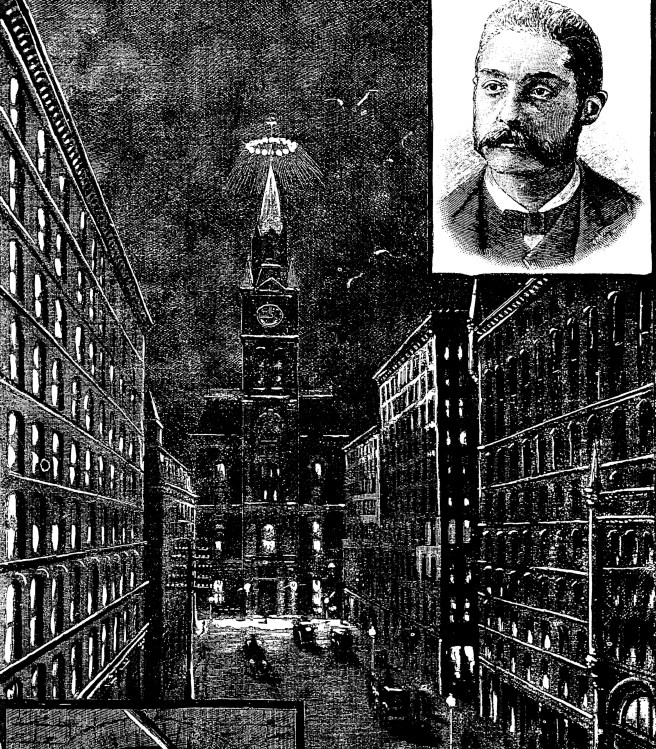

In 1885 Chicago did not have a building that expressed the skeleton frame as boldly as the Bank of Minneapolis. Note how large the operable panes of glass in the lower floors were…

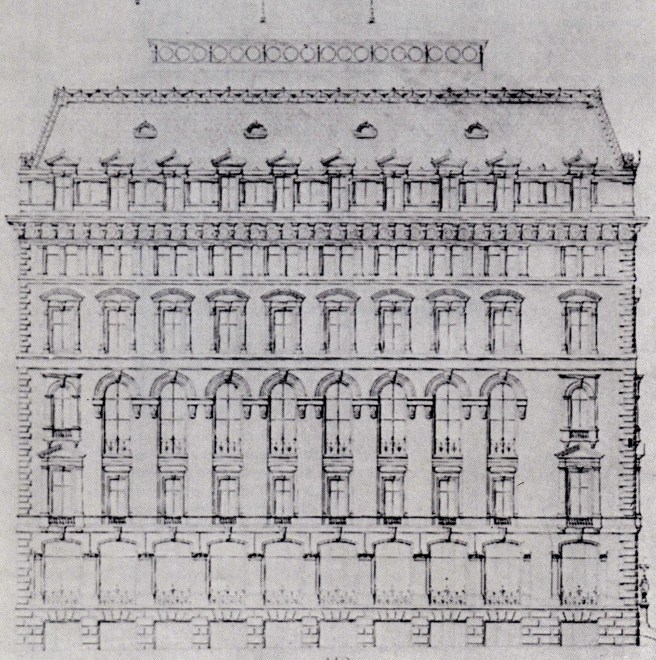

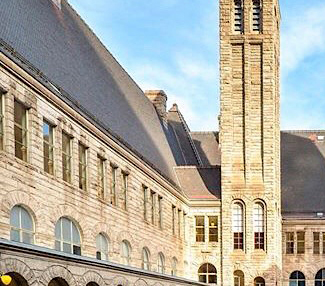

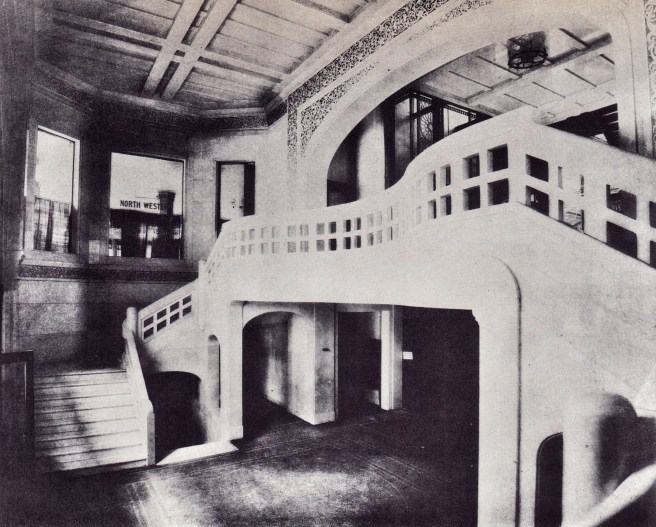

In 1888 E. Townsend Mix, (we last mentioned Mix in Sec. 3.7, where he had been the first architect to use P. B. Wight’s new terra cotta system in Milwaukee’s Mitchell Building in 1875) designed the 12-story Northwestern Guaranty Loan Building, the highlight of which was its 12-story atrium (and Chicago thought the just-completed Rookery was something special…). Unfortunately for the building’s owners, who wanted the tallest building outside of New York, the Pioneer Press in St. Paul hired S.S. Beman to design its 13-story building, This forced Mix to add a 40′ tall pavilion to the Northwestern Building, topping it off at 220,’ taller than any building in Chicago except the tower of the Board of Trade (this addition forced the owners of Chicago’s Auditorium to add two floors to its tower, increasing its height to 225′). Nonetheless, no Chicago building in 1888 had a 12-story atrium. Mix’s building had a 12-story atrium, and the atrium in Beman’s Pioneer Press was 13 stories high.

FURTHER READING:

Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl. H.H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1982.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)